- IP (Internet Protocol) https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc791.txt

- UDP (User Datagram Protocol) https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc768.txt

- TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc793.txt

- Official Arpa-internet Protocols https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc991.txt

- Address Allocation for Private Internets https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc1918.txt

- NAT - The IP Network Address Translator https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc1631.txt

- Traditional NAT - Traditional IP Network Address Translator https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc3022.txt

- STUN - Simple Traversal of User Datagram Protocol (UDP) https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc3489.txt

- NAT Behavioral Requirements for Unicast UDP https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc4787.txt

- NAT Behavioral Requirements for TCP https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc5382.txt

- NAT Behavioral Requirements for ICMP https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc5508.txt

互联网(Internet)起源于美国,最初由战争驱动技术发展。Internet 一词由 Interconnected networks 组合而成。

美国国防高级研究计划局(Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency),简称DARPA,是美国国防部属下的一个行政机构,负责研发用于军事用途的高新科技。成立于1958年,当时的名称是“高等研究计划局”(Advanced Research Projects Agency,简称ARPA),1972年3月改名为DARPA,但在1993年2月改回原名ARPA,至1996年3月再次改名为DARPA。

RFC 991 Official Arpa-internet Protocols 文档包含了 ARPA 官方协议的说明,按三个层次分类:

- NETWORK LEVEL

- HOST LEVEL

- APPLICATION LEVEL

互联网通信基于 IP 协议,此协议需要使用一个网络地址,即 IP 地址,早期的使用的 IPv4 地址使用 4 个字节,总共有 4,294,967,296 个地址。这些地址看似好多,但是全球都在使用,人均也分不到一个, 并且组建网络本身的设备也需要使用 IP 地址,还有些保留专用的地址,所以 IPv4 地址根本不够用。 最新的 IPv6 地址使用 128 bits (16 bytes),网络号、主机号各占 64 bits 8 个字节。并且, 网络号通常由 media access control (MAC) 或其它网络接口标识构成。显示为 8 组十六进制符号, 每组两个字节,每个 x 代表 4 bits:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx。 IPv6 地址支持压缩前导零的表示方法,每段连续的 0 也可以压缩为一个 0,多段的 0 值压缩为 :: 双冒号。注意的是:双冒号只能出现一次。

IP 地址包含网络号(Network number/ID)和主机号(Host number/ID),使用 32 bits 掩码来标记。 RFC 790/791 文档中将 32-bit 得 IP 地址根据不同网络号划分成三个类型:

Address Formats:

High Order Bits Format Class

--------------- ------------------------------- -----

0 7 bits of net, 24 bits of host A

10 14 bits of net, 16 bits of host B

110 21 bits of net, 8 bits of host C

111 escape to extended addressing mode

A 类地址最高位为 0,使用 7-bit 表示网络号 network number,24-bit 表示本地主机地址,可以分配 128 个 A 类网络。

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|0| NETWORK | Local Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

Class A Address 0.0.0.0 ~ 127.255.255.255

B 类地址最高位为 10,使用 14-bit 表示网络号,16-bit 表示本地主机地址,可以分配 16,384 个 B 类网络。

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|1 0| NETWORK | Local Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

Class B Address 128.0.0.0 ~ 191.255.255.255

C 类地址最高位为 110,使用 21-bit 表示网络号,8-bit 表示本地主机地址,可以分配 2,097,152 个 C 类网络。

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|1 1 0| NETWORK | Local Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

Class C Address 192.0.0.0 ~ 224.255.255.255

一些殊用途 IP:

-

回环地址(Loopback address)

-

网段地址 (Segment address)

-

广播地址(Broadcast address)

-

私有 IP 地址,在私有网络中使用的地址,不被公共互联网路由器转发。

RFC 1918 Address Allocation for Private Internets 文档简要地说明了保留的私用 IP 地址:

- Private Address Space

The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) has reserved the following three blocks of the IP address space for private internets:

10.0.0.0 - 10.255.255.255 (10/8 prefix) 172.16.0.0 - 172.31.255.255 (172.16/12 prefix) 192.168.0.0 - 192.168.255.255 (192.168/16 prefix) -

0.0.0.0(未指定地址):表示不确定的目标或任意目标。可用作服务器绑定地址,表示监听所有可用的网络接口。

-

255.255.255.255(广播地址):用于向本地网络中的所有设备广播消息。

-

169.254.0.0 ~ 169.254.255.255:用于自动配置 IP 地址,当设备无法通过 DHCP 获取有效的 IP 地址时,会使用此地址范围进行自我配置。

-

224.0.0.0 ~ 239.255.255.255:用于多播(Multicast)通信,允许将数据同时发送到多个设备。

网络号为 127 的地址都是回环地址,计算机用于自我回路测试和通信,也就是指向当前主机,例如 127.0.0.1。

127.0.0.0 表示网段地址,不能用于通信,执行 ping 127.0.0.0 只能得到“一般故障”。

主机标识段 Host ID 比特位为 1 的 IP 地址为广播地址,广播的分组传送给 Host ID 涉及的所有计算机。 例如,IP 地址 10.1.1.0,对应掩码 255.0.0.0,其网段广播地址为 10.255.255.255。向此广播地址 发送数据包时,它将被分发给该网段(10.0.0.0)上的所有计算机。

单播(Unicast)、多播(Multicast)和广播(Broadcast)是三种通信形式:

-

单播:两个网络节点之间的通信,此时信息的接收和传递只在两个节点之间进行。最普遍的通信形式,例如,收发电子邮件、浏览网页时,当前主机必须与邮件服务器、Web服务器建立连接,此时使用的就是单播数据传输方式。通常使用“点对点通信”(Point to Point)代替“单播”,因为“单播”一般与“多播”和“广播”相对应使用。

-

多播:也称为“组播”,网上视频会议、网上视频点播特别适合采用多播方式,一台主机同时为多台客户机提供服务。IP 网络的多播用专用的地址段,即 224.0.0.0 ~ 239.255.255.255 之间的 IP 地址,它们属于 D 类 IP 地址。

-

广播:一台主机主动向多台主机发送消息,在网络中的应用较多。如客户机通过 DHCP 服务自动获得 IP 地址的过程就是广播形式,向网段中的所有主机请求 IP 申请消息,而收到消息的主机中如果有 DHCP 服务器,就会响应客户端请求。同单播、多播相比,广播几乎占用了子网内网络的所有带宽。当网络中充斥无法处理的广播消息,就会形成“广播风暴”,蠕虫病毒和 ARP 攻击是造成网络广播风暴最主要的原因。IP 网络使用专用的广播地址,其中 255.255.255.255 是通用的广播地址,这个 IP 地址代表同一子网内所有的 IP 地址。

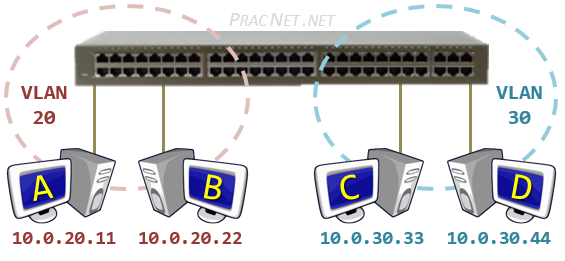

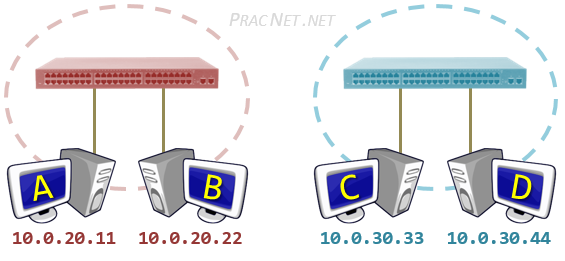

广播域(Broadcast domain)是指接收同样广播消息的节点的集合。在该集合中的任何一个节点传输一个广播帧,则所有其他能收到这个帧的节点都被认为是该广播帧的一部分。广播帧是指目标 MAC 地址 48 bits 全部为 1 的数据帧。不仅仅是广播帧,多播帧(Multicast Frame)和目标不明的单播帧(Unknown Unicast Frame)也能在同一个广播域中畅行无阻。

冲突域(物理分段)是连接在同一导线上的所有工作站的集合,或者说是同一物理网段上所有节点的集合或以太网上竞争同一带宽的节点集合。这个域代表了冲突在其中发生并传播的区域,这个区域可以被认为是共享段。冲突域看作是 OSI 模型中第一层的概念,连接同一冲突域的设备有 Hub、Reperter,或者其他进行简单复制信号的设备。也就是说,Hub、Repeater 等设备连接的所有节点可以被认为是在同一个冲突域内,它们不会划分冲突域。而第二层设备(网桥,交换机)第三层设备(路由器)都可以划分冲突域的,当然也可以连接不同的冲突域。简单的说,可以将Repeater等看成是一根电缆,而将网桥等看成是一束电缆。

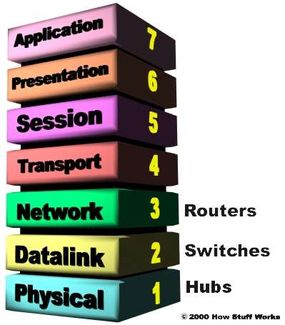

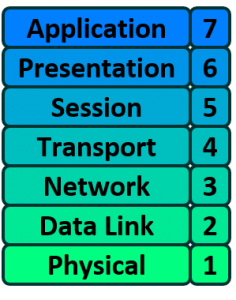

网络应用中使用模型概念:

| OSI 七层网络模型 | TCP/IP 模型 | 对应网络协议 |

|---|---|---|

| 应用层(Application) | 应用层 | HTTP、TFTP, FTP, NFS, WAIS、SMTP |

| 表示层(Presentation) | 应用层 | Telnet, Rlogin, SNMP, Gopher |

| 会话层(Session) | 应用层 | SMTP, DNS |

| 传输层(Transport) | 传输层 | TCP, UDP |

| 网络层(Network) | 网络层 | IP, ICMP, ARP, RARP, AKP, UUCP |

| 数据链路层(Data Link) | 数据链路层 | FDDI, Ethernet, Arpanet, PDN, SLIP, PPP |

| 物理层(Physical) | 硬件 | IEEE 802.1A, IEEE 802.2 ~ IEEE 802.11 |

网络应用开发需要理解 OSI 分层概念,特别是 Layer 2 ~ 4,它们与 TCP/IP 编程模型关系密切:

-

OSI Layer 1 – Physical

物理层对应的是网络的连接介质,通过电缆、光纤、中继器(Repeaters)、集线器(Hubs) 传输比特码,即 1、0 电脉冲信号(the 1’s and 0’s)。

中继器用于直接转发电脉冲信号,并且可以补偿信号在传输过程中的衰减。集线器相当于多口中继器,各个端口的信息互通。

-

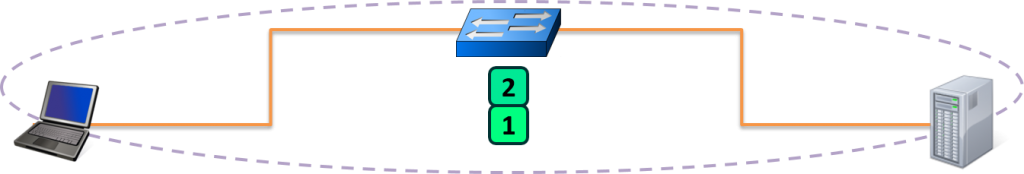

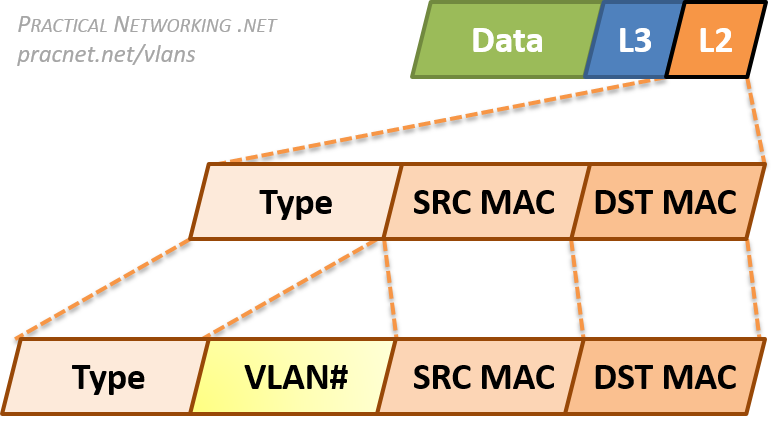

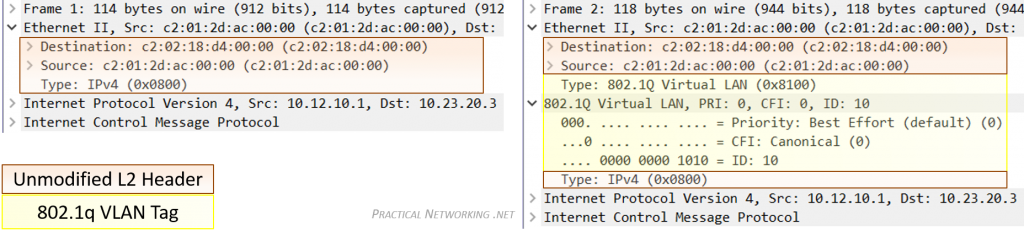

OSI Layer 2 – Data Link

数据链路层,Data Link layer,响应 OSI 物理层接口。实际上,数据链路负责在电缆、光纤上放置、接收 1、0 电脉冲信息(the 1’s and 0’s)。网卡(NIC - Network Interface Card)上插入的以太网电缆就是对应数据链路层的功能,比特脉冲信息通过电缆上传递,接收和发送。对于无线网卡(WIFI NIC),也以同样方式传递比特信号,只不过是无线电波替代了电缆上的电脉冲。

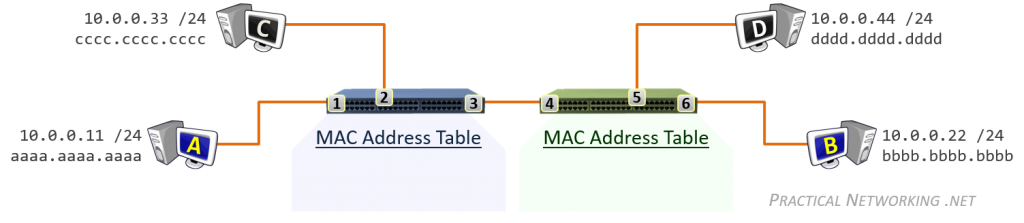

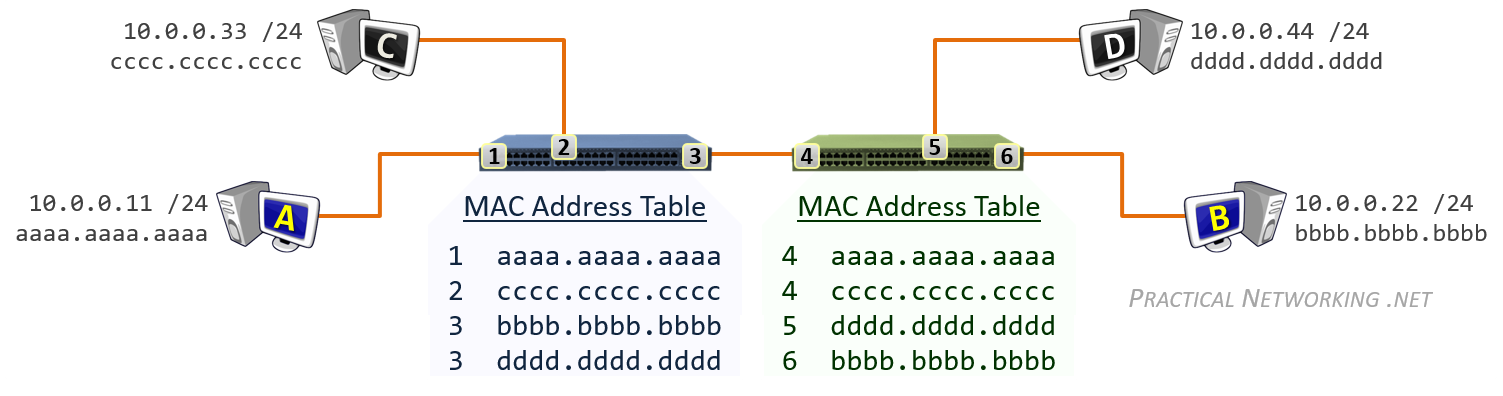

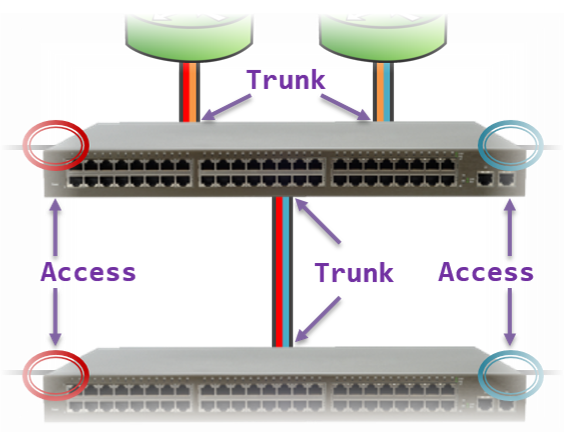

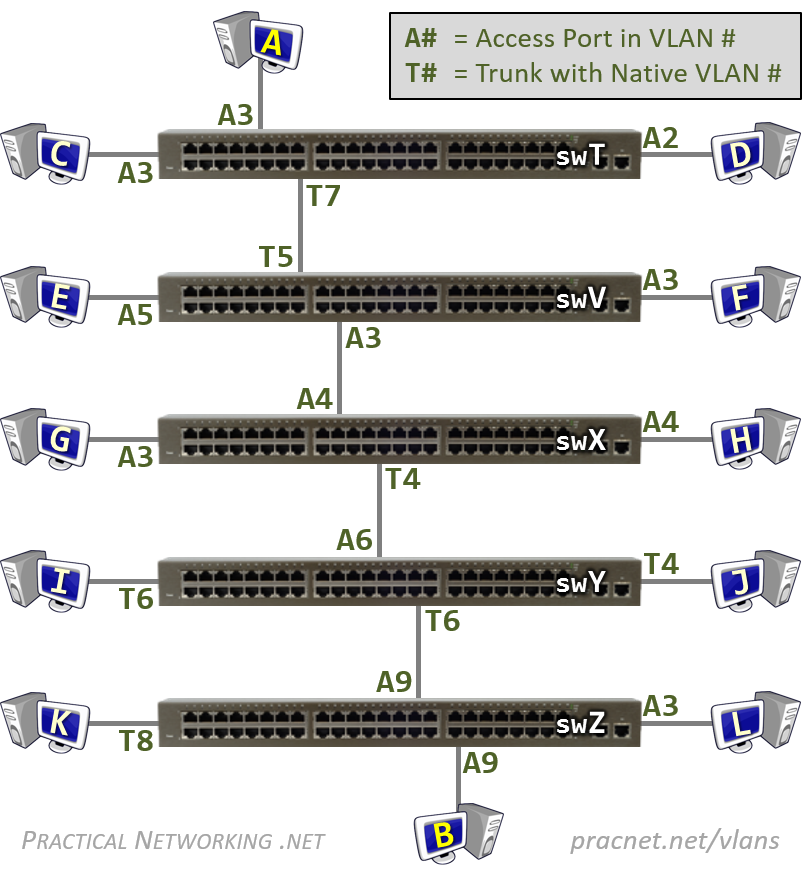

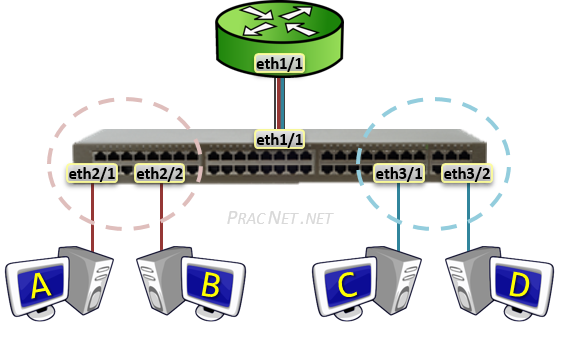

除了 NIC,交换机(Switch)也工作在数据链路层,交换机的主要职责是负责协调本网络的通信,包括:

- Learning 学习网络拓扑结构

- Flooding 流量控制

- Forwarding 数据转发

- Filtering 数据过滤

数据链路层收发的比特数据对应的是数据帧(Frame),此层寻址系统是物理地址(MAC - Media Access Control),使用 48 bits 共 6 个字节表示。MAC 地址在硬件厂商生产过程中就已经确定,有时也称为硬件地址,或者 Burned In Address (BIA)。

ipconfig -all; sleep 30总结:数据链路层通过 NIC 之间的电缆或无线信号收发数据帧,数据收发 hop to hop,每个 NIC 对应跃点(Hop)。

-

OSI Layer 3 – Network

网络层逻辑上使用 IP 协议地址来确实网络上的节点(端点,end),因此数据包的传输形式是 end to end。不同于固定(绑定)在硬件内的 MAC 地址,IP 是临时分配的地址。路由器作为网络连接中主要角色,其工作于网络层,协调网络之间的通信,这一点与交换机区别。因此,路由器对应着两个网络之间的一个边界。要与其它网络的设备通信,就必需经过路由器。

-

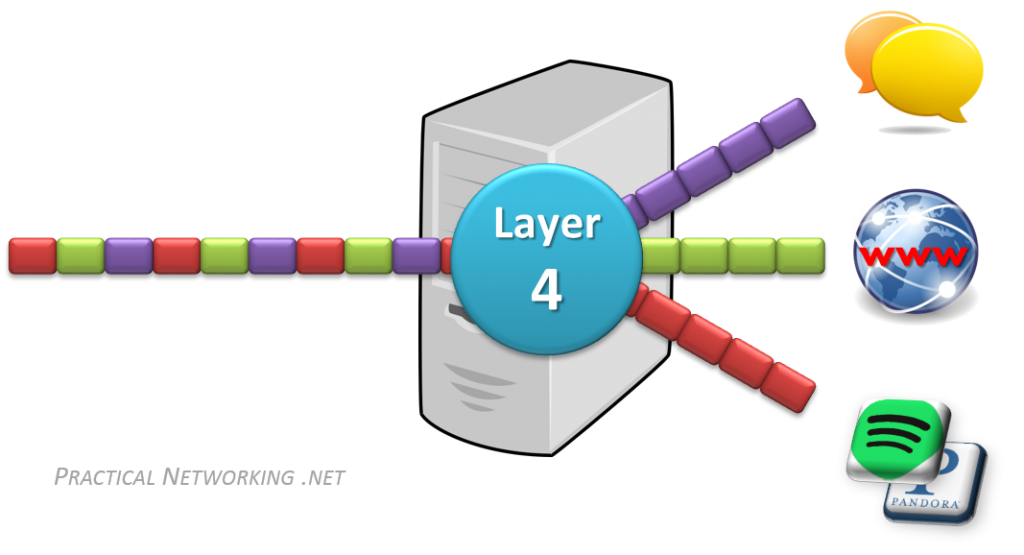

OSI Layer 4 – Transport

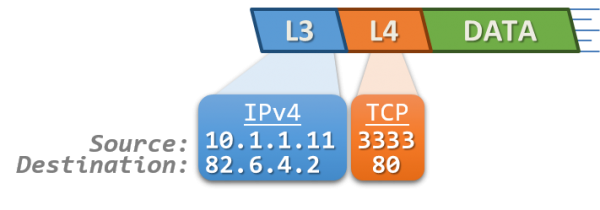

传输层对应的是网络流量,数据在计算机网卡 NIC - Network Interface Card 中以补码、反码(1’s and 0’s)形式表示。这些数据流可能是浏览器中看到的 Web 页面、Email 中阅读的内容、网络音乐播放器中的声音。为了区分这些网络流量,传输层就引入了 PORT,对应的是 TCP/UDP 协议中使用的端口,两协议各自使用 32 bits 数据表示端口,可以表达 65,536 个端口。TCP/UDP 端口是其一种网络传输标识符(Transport identifier),还有 ICMP query ID,也是。系统通过数据包中的 IP 地址(来源地址、目标地址)和 TCP/UDP 的端口组合来区分数据流属于什么应用程序。

总结来说,如果 Layer 2 对应 hop to hop 的数据传输,Layer 3 对应 end to end 的数据传输,那么 Layer 4 就对应 service to service 的数据传输。TCP/UDP 和 Port 是传输层的标志,也是网络应用开发人员主要的网络基础知识。

-

OSI Layer 5, 6, 7 - Session, Presentation, Application

会话层、表示层、应用层是 OSI 模型在数据呈送给最终用户前的最终阶段。对于一个纯粹的网络工程师而言,区别对待这三层的意义不大。反而使用 TCP/IP 模型更有意义,它们统一作为应用层看待,对应的就是应用程序中 socket 编程接口收发的数据。工程师们常用 L5-7 或 L5+ 或 L7 这样的简化形式表达。

理解以上 OSI Model 基础后,作为网络开发工程师,就需要对 Layer 2 ~ 4 有深刻的认识,即对应 IP、MAC/TCP、UDP/Port 三层内容。其中 Layer 2 ~ 3 又更贴近硬件层面,也更贴近计算机网络通信的核心,它们对应了计算机网络最重要的两个寻址系统:

- Layer 2 使用 MAC 地址,负责 hop to hop 的数据包收发;

- Layer 3 使用 IP 地址,负责 end to end 的数据包收发;

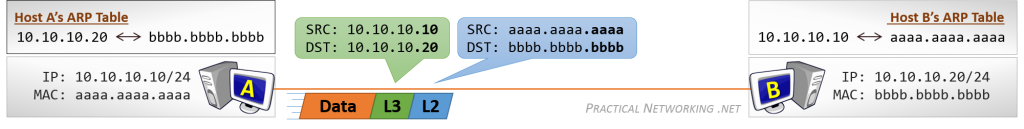

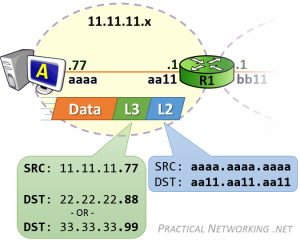

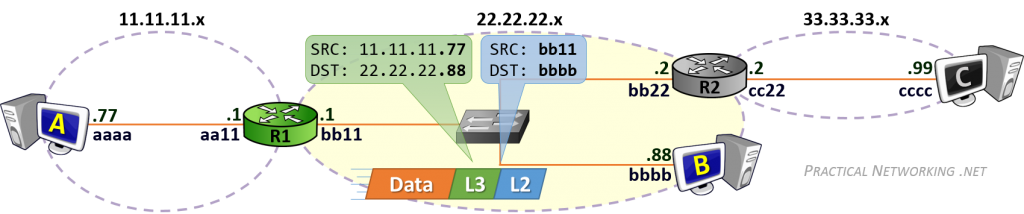

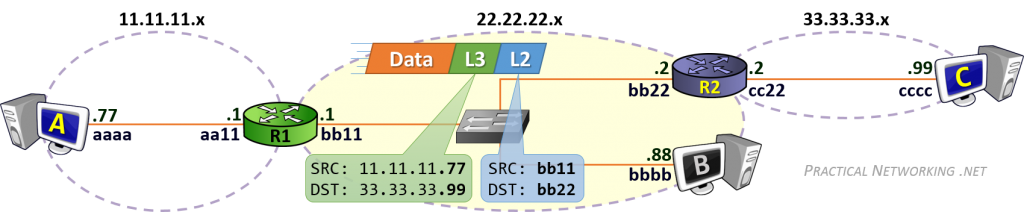

当计算机需要发送数据时,需要先将数据包装到 IP 包中,IP 包头部包含通信双端(end to end)的 IP 地址(Source IP 和 Destination IP)。然后再继续打包到 MAC 数据帧(Frame),其帧头部包含了通信双方(hop to hop)的 MAC 地址(Source MAC 和 Destination MAC)。

在网络传输过程中,IP 地址或者 MAC 地需要根据实际情况进行变更。数据的接收方,包含 MAC 地址的数据帧(Frame)头部会在路由上剥离,并按路由表记录的下一个 hop 的数据重新生成数据帧头部。当数据包到达最终的目标计算机时,IP 包的头部才被剥离,并完成端到端的传递。以下动画图中涉及 5 个跃点中的四个不同的 MAC 头每一个都处理了“跳到跳”的传递,最后一个不需要。

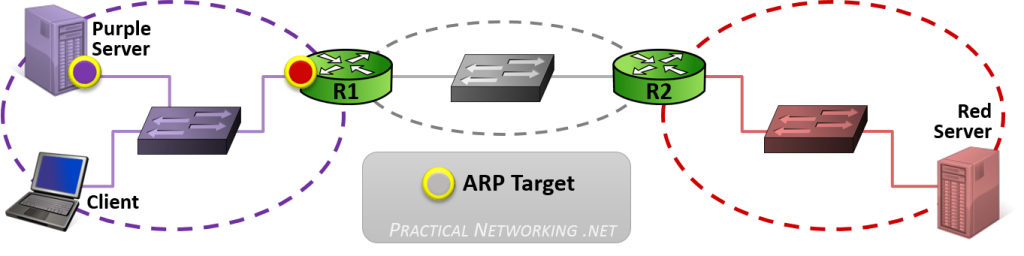

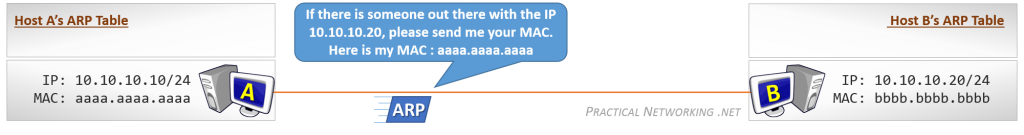

通常,通信双方是知道 IP 地址,但是可能不知道 MAC 地址,在网络层引入了一个 Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) 协议用于探测 MAC 地址。主机上使用 ARP Table 存储 IP 与对应 MAC 地址的关系。

PracNet.net Key Players 文章中的总结非常明了,网络中的主体角色(Hosts, Network, Switches, Routers)与 OSI 模型的关系。

OSI model, Specifically:

- [OSI Layer 1 is the physical medium carrying the 1’s and 0’s across the wire

- [OSI Layer 2 is responsible for hop to hop delivery and uses MAC addresses

- [OSI Layer 3 is responsible for end to end delivery and uses IP Addresses

- [OSI Layer 4 is responsible for service to service delivery and uses Port Numbers

Key Players involved in moving a packet through the Internet:

- Switches facilitate communications within networks and operate at Layer 2

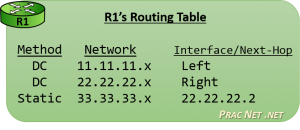

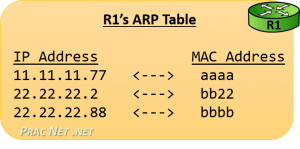

- Routers facilitate communication between networks and operate at Layer 3

- ARP uses a known IP address to resolve an unknown MAC address

Three different tables that are use to store different mappings:

- Switches use a MAC Address Table which is a mapping of Switchports to connected MAC addresses

- Routers use a Routing Table which is a mapping of known Networks to interfaces or next-hop addresses

- All L3 devices use an ARP Table which is a mapping of IP Addresses to MAC addresses

网络是用物理链路将工作站或主机相连在一起,组成数据链路,从而实现资源共享和通信。这里的物理链路 不仅仅指的是能够看到的双绞线、光纤,也可能是无线电波,如何联接取决于使用什么通信技术。连接起来的 网络又可以通过一些中间设备(或中间系统)连接起来,术语称之为中继(relay)系统。有以下五种中继系统:

- 物理层(OSI Layer 1)中继系统,即中继器(repeater)。

- 数据链路层(OSI Layer 2),即网桥或桥接器(bridge)。

- 网络层(OSI Layer 3)中继系统,即路由器(router)。

- 桥路器(brouter),兼有网桥、路由器的功能。

- 在网络层以上的中继系统,即网关(gateway)。

OSI - Open Systems Interconnect 模型标准由国际标准化组织(ISO)提出的一个试图使各种计算机在世界范围内互连为网络的标准框架。

网段(Network segment)一般指一个计算机网络中使用同一物理层设备(传输介质,中继器,集线器等) 能够直接通讯的那一部分,列如一般家庭中使用的局域网。以下是常见的网络概念:

- 路由器: 连接不同子网的设备,负责寻径和转发(routing),工作在 OSI 的网络层。

- 网桥、中继器(Repeaters):连接不同子网,使其透明通信,工作在数据链路层,解析数据帧,存在“广播风暴”。

- 集线器(Hub): 集线器的基本功能是信息分发,任一个端口接收的信号向所有端口分发出去。

- 网关:工作在应用层,不同子网间的翻译器,对收到的信息进行重新打包。

转发器作为中继系统时,连接起来的网络一般不称之为网络互联,因为这仅仅是扩大一个网络,仍然是一个网络。 高层网关由于比较复杂,目前使用得较少。因此,讨论网络互连时,一般都是指用交换机和路由器进行互联的网络。

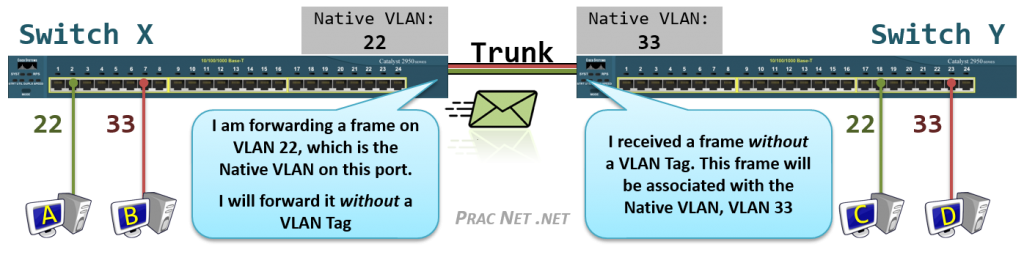

网关(gateway)是逻辑层面的概念,能帮助主机转发三层数据包的就叫网关,主机的网关地址所在的设备。 网关可以是是路由器,也有可能是一个开了路由转发的服务器、三层交换机(支持物理层、数据链路层及网络层协议)。 三层交换机可以解决 Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs) 组网,由于不同 VLAN 间不能直接通信, 因为它们通常归属不同的网段,不在同一个广播域。如果是 LANs 的话,直接连接到路由器物理 LAN 端口, 配个路由表就能通了。但是 VLANs 可能在一个物理 LAN 端口,这怎么配路由?三层交换机就诞生了, 三层交换机设置了虚拟 LAN 端口,专供 VLAN 使用,保证 VLAN 间的通信。

使用 IP 通信时,除了包含网络号和主机号的 IP 地址,还有 32 bits 端口号,这些信息在网络中用于 确定通信双方,端口号工作在 OSI 应用层,用于确定通信中的应用程序。其中 0 ~ 1023 为保留端口, 供常用的应用使用,例如 80 端口用于 Web 服务,浏览器使用默认的 80 端口访问 Web 内容, 也可以显式提供端口: https://baidu.com:80/ 。其中域名需要通过 DNS - Domain Name System 服务器解释得到对应的已登记的 IP 地址。网络设备本身还有一个 MAC 地址,它们对应关系如下:

- Transport address (TCP/UDP port): app-level conversation

- Network-level address (IP address): point of attachment

- Link-level address (MAC address): device

IP 地址、端口号会打包到对应协议的数据包中的头部,并通过网络链路传递。在一个网络中,所有 IP 地址 都唯一地标识一台设备,同一网络中不可以有多个设备拥有同一个 IP 地址。同网段中的设备可以直接通信, 其数据包中。按协议依赖关系,数据包会层层打包、解包,TCP 基于 IP 协议,TCP 数据包中就包含 IP 包。

域名的解释是透明的,用户并不需要知道这一过程,网络通信开始之前,网络开发接口会先向 DNS 服务器 查询域名对应的 IP 地址,然后将 IP 地址封装到数据包的头部。参考文档:

- DOMAIN NAMES - CONCEPTS AND FACILITIES

- DOMAIN NAMES - IMPLEMENTATION AND SPECIFICATION

- DNS Terminology

- DNS Client .Net Web App

- BIND (Berkeley Internet Name Domain)

- Computer Systems Fundamentals - 5.8. Extended Example: DNS Client

Internet Header Format

A summary of the contents of the internet header follows:

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|Version| IHL |Type of Service| Total Length |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Identification |Flags| Fragment Offset |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Time to Live | Protocol | Header Checksum |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Source Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Destination Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Options | Padding |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

Example Internet Datagram Header

Figure 4.

Note that each tick mark represents one bit position.

Version: 4 bits

The Version field indicates the format of the internet header. This

document describes version 4.

IHL: 4 bits

Internet Header Length is the length of the internet header in 32

bit words, and thus points to the beginning of the data. Note that

the minimum value for a correct header is 5.

TCP Header Format

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Source Port | Destination Port |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Sequence Number |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Acknowledgment Number |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Data | |U|A|P|R|S|F| |

| Offset| Reserved |R|C|S|S|Y|I| Window |

| | |G|K|H|T|N|N| |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Checksum | Urgent Pointer |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Options | Padding |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| data |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

TCP Header Format

Note that one tick mark represents one bit position.

Figure 3.

- https://github.com/fatedier/frp

- https://github.com/samyk/pwnat

- https://www.kali.org/tools/pwnat/

- pwnat, by Samy Kamkar - http://samy.pl/pwnat

- TCPIP Illustrated, Volume 1 The Protocols by Kevin R. Fall, W. Richard Stevens - Chapter 7 Firewalls and Network Address Translation (NAT)

- Computer Systems Fundamentals - 1.4.2. Peer-to-peer (P2P) Architectures

- P2P技术详解(一):NAT原理、P2P简介 http://www.52im.net/thread-50-1-1.html

- Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs) https://www.practicalnetworking.net/stand-alone/vlans/

- Network Address Translation (NAT) https://www.practicalnetworking.net/series/nat/why-nat/

- How NAT traversal works by David Anderson https://tailscale.com/blog/how-nat-traversal-works

相同网段中的主机可以直接进行通信,只需要将通信双方的 IP 地址、端口打包到 TCP/IP 数据包中即可。 IP 包头部记录的 Source Address 和 Destination Address 对应通信的发起方、接收方。端口 信息记录在 TCP/UDP 数据包头部,以确定通信的应用程序。

当不同网段中的主机进行通信时,首先需要经过网关,IP 数据包 Destination Address 也只能 填写对方的网关 IP 地址,不能直接填写对方的 IP 地址,因为此 IP 地址只用于对方所在的网段。 后续再进行转发,就像火车换乘,或者转机。

网民通过互联网服务提供商(ISP - Internet Services Provider)提供的网关接入互联网, 入户的路由对应的是本地局域网,经过网关后连接到互联网。以下是基本的跨网段通信形式:

- 公网与局域网间的主机通信,需要内网穿透(Intranet Penetration);

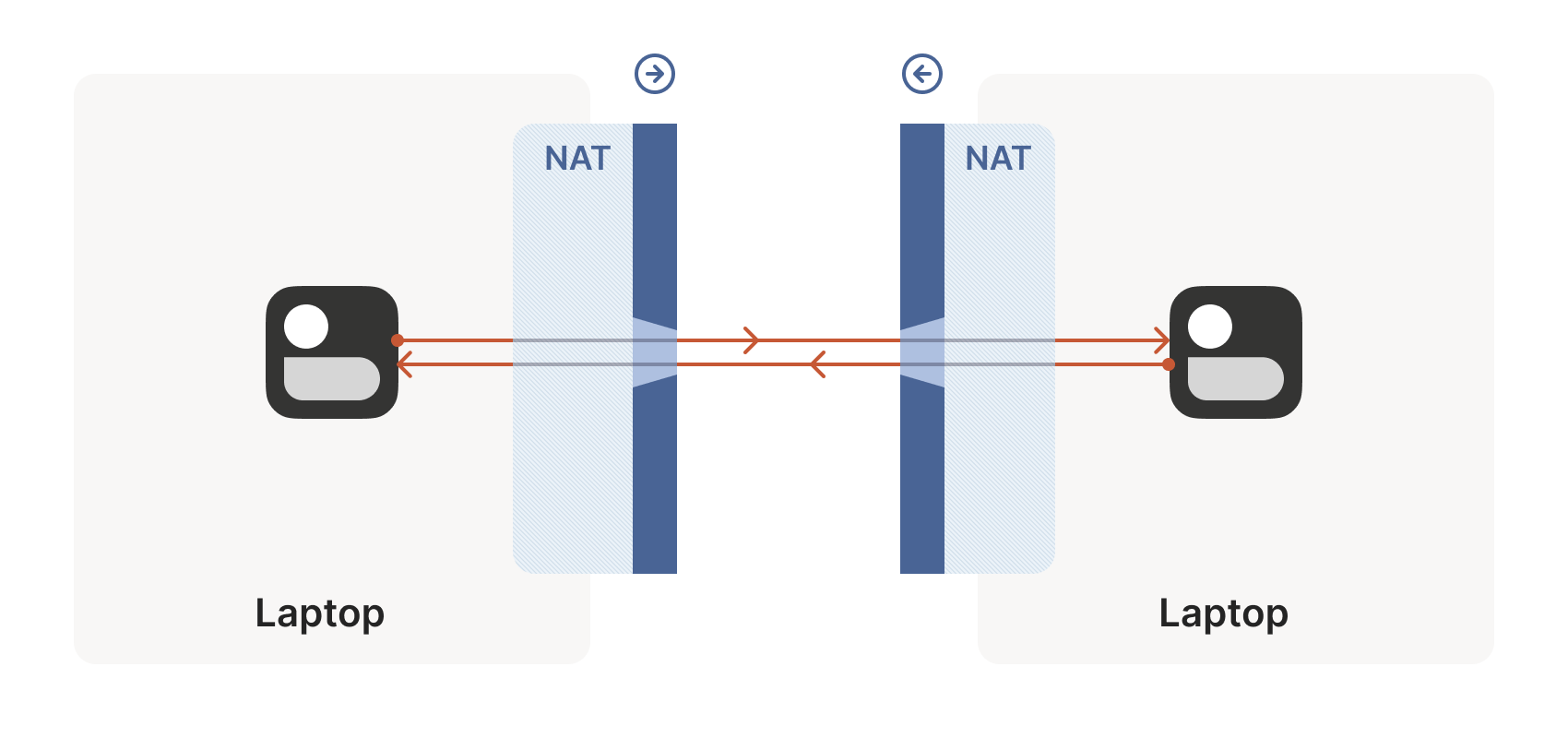

- 连接到公网中的局域网主机间的通信,中间经过多个 NAT 映射,需要进行 NAT 穿透(NAT traversal);

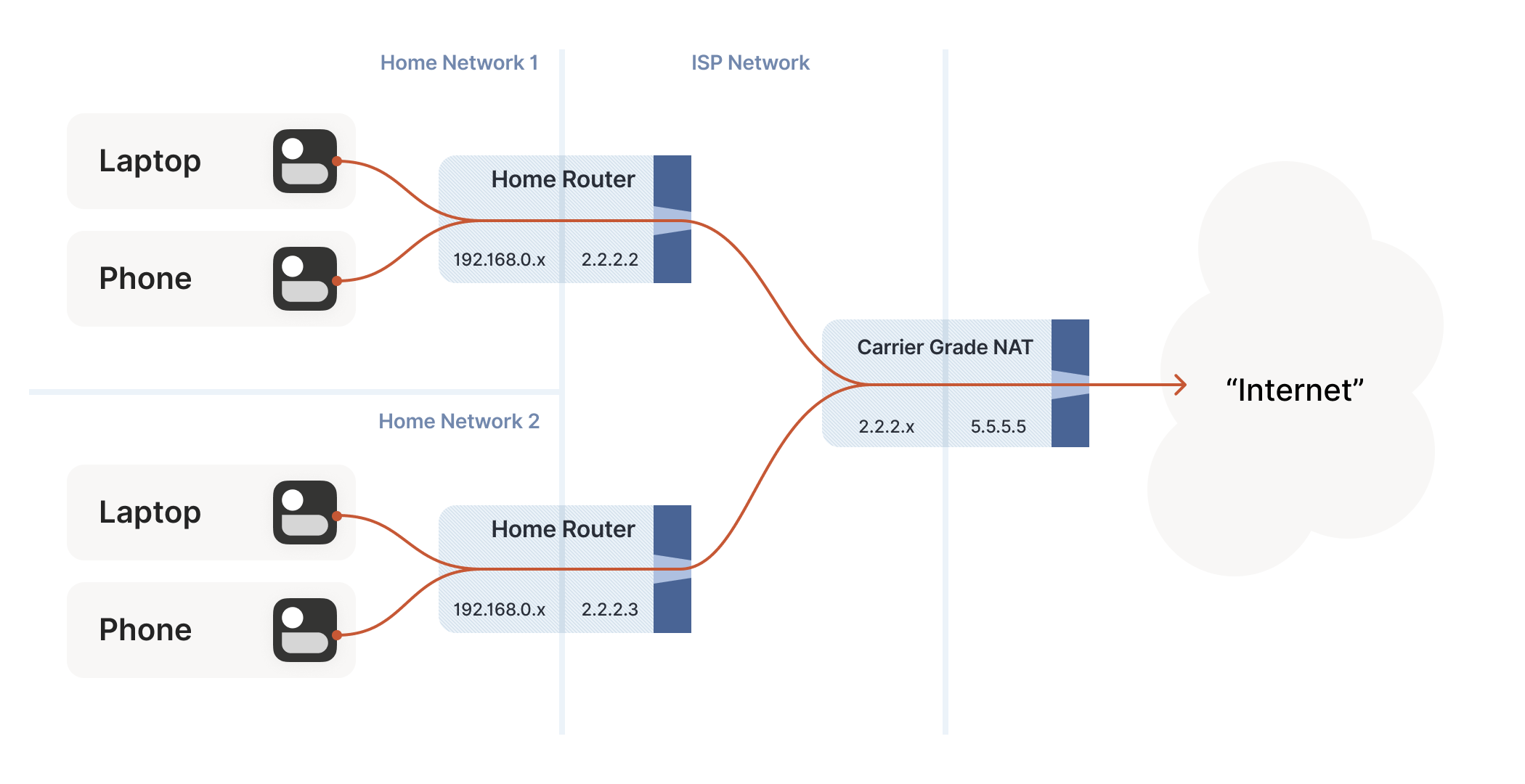

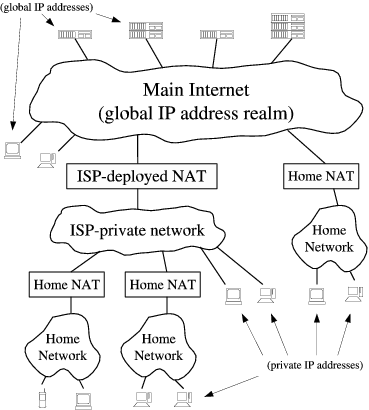

IP 网络设计初期使用的 IPv4 所能表达的独立 IP 地址虽然有 42 亿多个,但是随着互联网的快速扩展,很快就出现 IP 耗尽的问题。为了能继续扩大联网规模,Cisco 系统公司开发出了 NAT 技术,通过 NAT 进行 ip:port 地址映射,可以将私网连接到公网。通过地址映射,NAT 使私网中多个设备共享公网上的同一地址,因此即使面临 IPv4 地址短缺的问题,仍然能不断扩张互联网的规模。

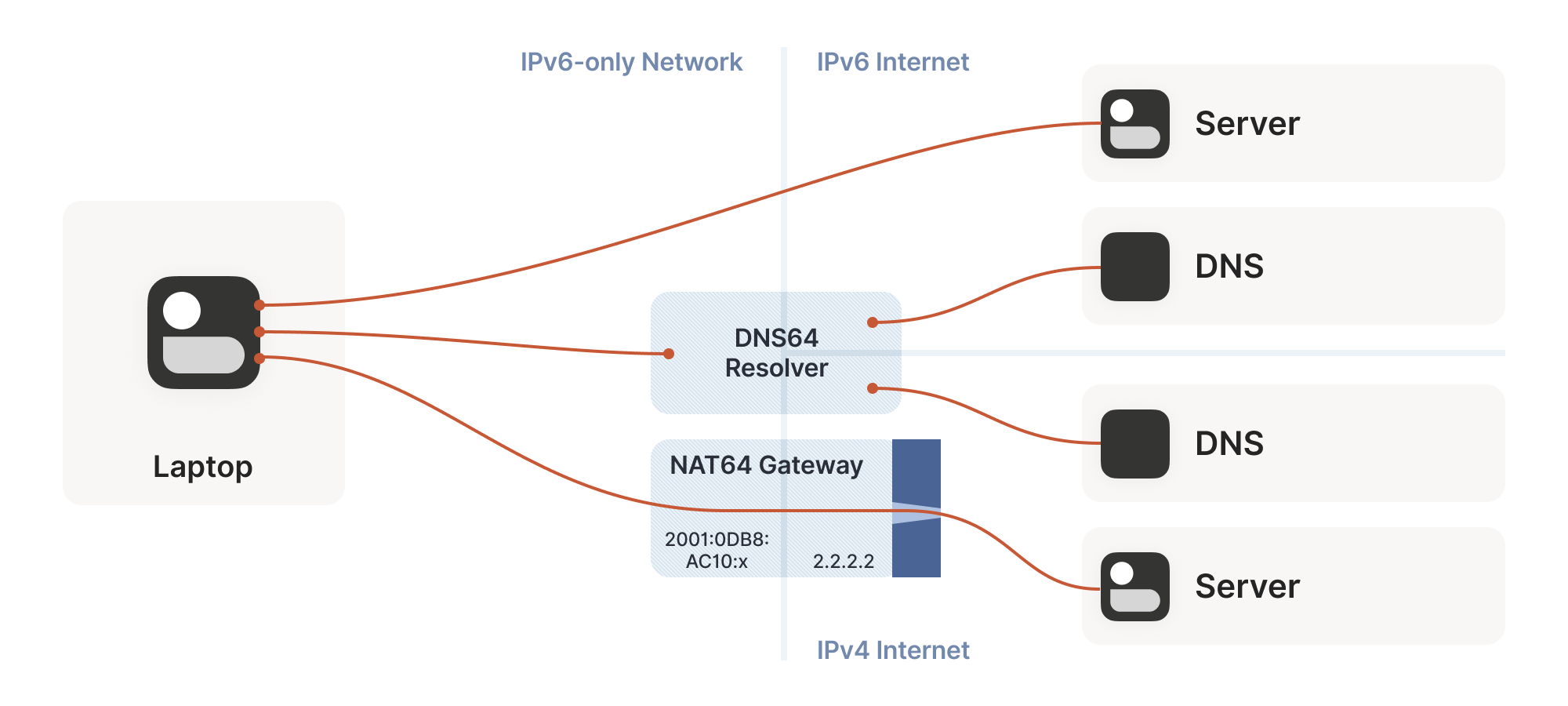

IPv6 时代还需要 P2P 技术吗?需要的,因为私有网络的需求不会因为公网 IP 够用而消失。NAT、防火墙(firewall)始终是最基础的网络组件,ALG 这类应用层协议,需要嵌入到 NAT 设备。出于安全和隐私的考虑,互联网被分割成子网。基本子网段如下:

- 外部公共网络:通常是指公共/全球互联网或各种外部网。

- 内部专用网络:定义为家庭网络、公司内部网和其他“封闭”网络。

- 边界网络:由堡垒主机组成,堡垒主机是安全性经过强化的计算机主机,可以有效抵御外部攻击。

P2P 在即时通讯方案中应用非常广泛,比如 Massively Multiplayer Online games (MMOs) 游戏的玩家连线协作对抗游戏环境(PVE)或者玩家之间对战(PVP),IM 应用中的实时音视频通信、实时文件传输甚至文字聊天等。网络中的主机可能来自不同的网络,它们通过互联网连接在一起,彼此都没有公网 IP 地址,不能直接连接。P2P 要解决的一个问题就是如何让位于不同网络的主机进行直接的连接通信,解决问题的方法是 NAT 穿透。

P2P 网络连接就需要借助网关的功能:

- 数据转发:网关接收来自源网络的数据包,并根据数据包 Dest IP 地址决定发送到哪个网段。

- 路由选择:根据各种路由协议来学习网络拓扑和路由信息,并根据这些信息生成路由表、决定数据包的路由选择。

- 地址转换:NAT Gateway 功能,数据包从一个网络转发到另一个网络时,网关可以修改数据包的 IP 地址和端口。

- 数据过滤和安全:可以根据源地址、目标地址、端口号等信息来决定是否允许或拒绝数据包的传输。

假设以下网络,NAT 网关拥有公网端口的 IP 地址 22.20.20.1,私网 LAN 端口 IP 地址 192.168.0.1。私网其中一台主机 A 192.168.0.2 向公共网中的主机 S 202.20.65.7 通信的流程:

+--+

|--|

/____\

S 202.20.65.7

|

WAN --------------------|--------------------------

\ | / |

+-------------+------------+

| 22.20.20.1 |

| Stub Router with NAT |

| 192.168.0.1 |

+----+-----------------+---+

| |

LAN -----------|-----------------|-----------------

+----------+-----------------+------------+

| | | |

| +--+ +--+ |

| |--| |--| |

| /____\ /____\ |

| A 192.168.0.2 B 192.168.0.3 |

+-----------------------------------------+

- A 向 S 发送一个 IP 包

192.168.0.2=>202.20.65.7 - NAT Gateway 修改 IP 包进行地址影射

22.20.20.1=>202.20.65.5 - S 响应 A 一个 IP 包,目标地址是 Gateway 的公网地址

202.20.65.5=>22.20.20.1 - NAT Gateway 根据映射记录,修改 IP 包目标地址,影射到 A 主机

202.20.65.5=>192.168.0.2

IP 包首先经过 NAT 网关,IP 包的 Src IP 会被替换成 NAT Gateway 公网 IP 22.20.20.1 并转发到公共网,此时 IP 包已经不含任何私有网 IP 的信息。公网主机 S 202.20.65.5 收到 IP 包后进行响应,相应 IP 包将被发送到 Gateway,并由它转递给私网的 A 主机。这时,Gateway 会将 IP 包的目的 IP 转换成私有网中 A 主机的 IP 并转发给私网目标主机 A。对于通信双方而言,NAT 地址的转换过程完全透明。

以上是经典的 C/S 架构,Client 与 Server 之间通信,通常服务器架设在公网,为接入公网的主机提供服务。 P2P - Peer-to-Peer 网络技术区别于 C/S 架构,不需要专用的服务器,加入 P2P 网络的所有主机 都可以进行端到端的通信。

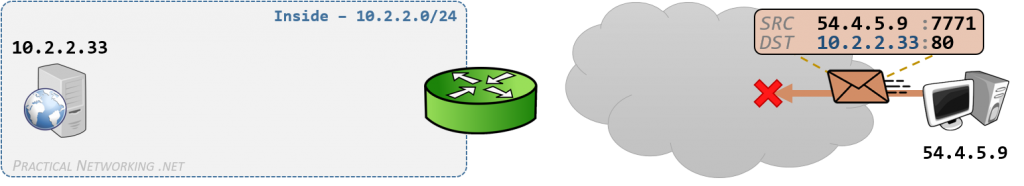

C/S 构架中,服务器通常拥有公网 IP 地址,客户端位于私有网络,因为网关存在传统 NAT 功能(Traditional NAT),只需要客户端向服务器发起连接就可以通信。例如,使用浏览器访问 Web 服务器。如果公网主机需要连接私网主机,那么就需要将私网主机暴露给公网,这就是“内网穿透”。

内网穿透,简单地说就是让外网可以获取内网的数据,通过 NAT 协议将内网地址映射到公共网络上, 这样就可以在公共网络上访问内网的数据。可以配置 NAT 映射规则实现。常用的有 frp 内网穿透、花生壳、Cpolar 等工具。

以下是 RFC 3022 总结的传统 NAT 映射形式的两种变体:

- Basic NAT Operation

- Network Address Port Translation (NAPT) Operation

Stub 一词表示网络末端,Stub border 即分隔公网与私网的结界,Stub A 表示一个私有专用网络(网段),等同未稍网域 stub domain。数据包传递方向使用 ^ 和 v 符号表示,源地址、目标地址分别使用 s 和 d 表示。

传统 NAT 功能(Traditional NAT)是最基本的 NAT 映射功能,私网主机可以通过它直接连接到公网的主机。传统 NAT 的功能就是进行地址转换(Address Translation),通常是从私网出站的单向连接(uni-directional, outbound)。在特殊情况下,可以允许相反的方向连接,需要设置预选主机的静态地址映射。Basic NAT 和 NAPT 是传统 NAT 的两种变体。Basic NAT 中的转换仅限于 IP 地址,而 NAPT 中的转换则包括 IP 地址和传输标识符,如 TCP/UDP 端口或 ICMP 查询 ID。根据是否是修改源地址或目标地址,NAPT 双细分为 SNAT - Source NAT 和 DNAT - Destination NAT。

互联网协议(IP)早期用于互联互通的 CateNet 网络模型中进行主机到主机的数据报服务。连接设备的网络称为网关,这些网关通过 Gateway to Gateway Protocol (GGP) 协议进行通信,以实现控制目的。例如,网关或目标主机将与源主机通信中,报告数据报处理中的错误。为此,使用互联网控制消息协议(ICMP)。ICMP 基于 IP 的基本支持,就像它是一个更高层次的协议一样,然而,ICMP 实际上是 IP 的一个组成部分,需要各个 IP 模块实现。

2. Overview of traditional NAT

\ | / . /

+---------------+ WAN . +-----------------+/

|Regional Router|----------------------|Stub Router w/NAT|---

+---------------+ . +-----------------+\

. | \

. | LAN

. ---------------

Stub border

Figure 1: Traditional NAT Configuration

2.1. Overview of Basic NAT

\ | /

+---------------+

|Regional Router|

+---------------+

WAN | | WAN

| |

Stub A .............|.... ....|............ Stub B

| |

{s=198.76.29.7, ^ | | v {s=198.76.29.7,

d=198.76.28.4} ^ | | v d=198.76.28.4}

+-----------------+ +-----------------+

|Stub Router w/NAT| |Stub Router w/NAT|

+-----------------+ +-----------------+

| |

| LAN LAN |

------------- -------------

| |

{s=10.33.96.5, ^ | | v {s=198.76.29.7,

d=198.76.28.4} ^ +--+ +--+ v d=10.81.13.22}

|--| |--|

/____\ /____\

10.33.96.5 10.81.13.22

Figure 2: Basic NAT Operation

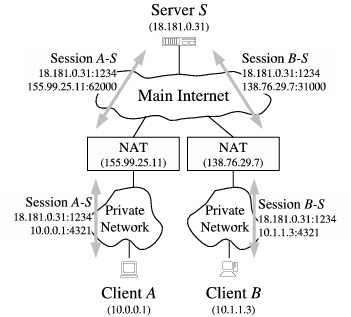

以上示意图假定是家庭网络的通信,左侧主机经过家用路由器出站,执行 SNAT。数据包经过路由器时, 路由器发现这是一个它没有见过的新会话(session)。它知道 10.33.96.5 是私有网络 IP,公网无法 给这样的地址回包。解决办法:路径由添加一个路由映射规则,将自身拥有的 IP 198.76.29.7 映射到 私有网络主机地址。并且将出站的数据包中的源地址 s 更改为自身的 IP。

数据包进入公网,并传递到目标主机。目标主机答复时,将向 Stub A 路由 IP 及指定的端口发送数据。 路由器收到数据包,并根据包含的目的地址匹配到路由映射规则,并将数据包发送给私有网络中的最终目标主机。

2.2. Overview of NAPT

\ | /

+-----------------------+

|Service Provider Router|

+-----------------------+

WAN |

|

Stub A .............|....

|

^ {s=138.76.28.4,sport=1024, | v {s=138.76.29.7, sport = 23,

^ d=138.76.29.7,dport=23} | v d=138.76.28.4, dport = 1024}

+------------------+

|Stub Router w/NAPT|

+------------------+

|

| LAN

--------------------------------------------

| ^ {s=10.0.0.10,sport=3017, | v {s=138.76.29.7, sport=23,

| ^ d=138.76.29.7,dport=23} | v d=10.0.0.10, dport=3017}

| |

+--+ +--+ +--+

|--| |--| |--|

/____\ /____\ /____\

10.0.0.1 10.0.0.2 ..... 10.0.0.10

Figure 3: Network Address Port Translation (NAPT) Operation

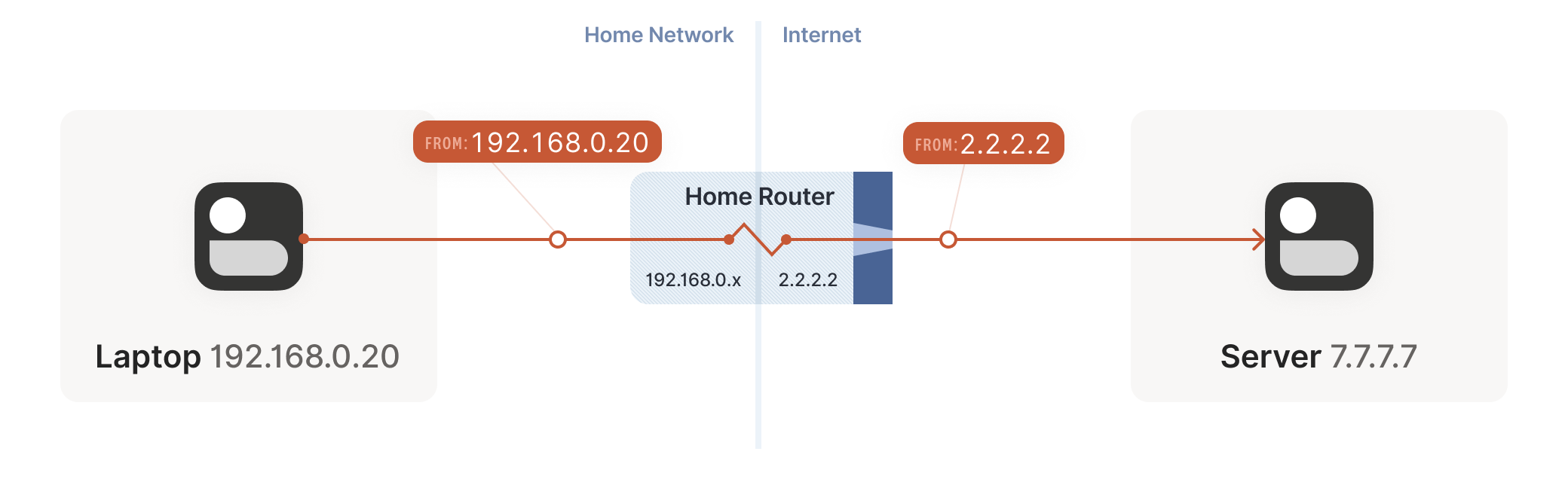

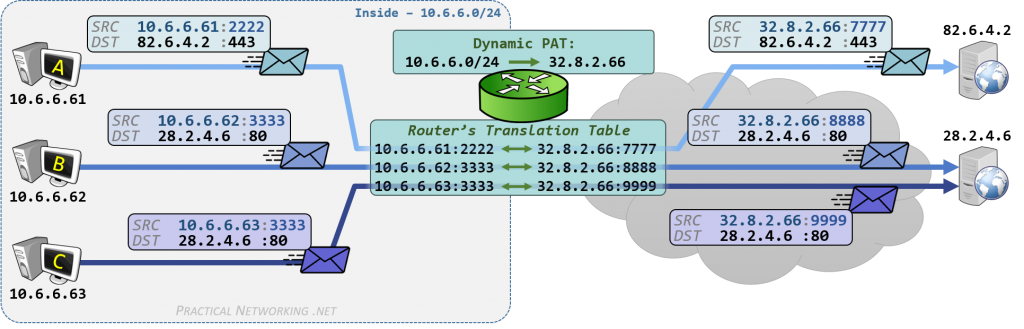

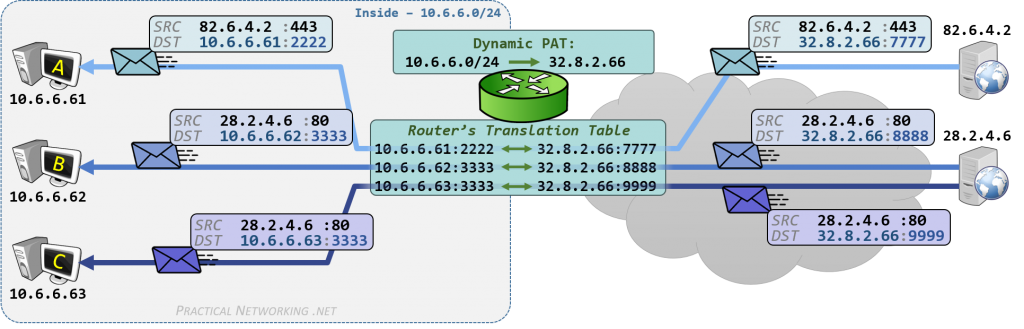

NAPT 方式中,将使用 IP 加端口的映射方式,路由表记录的映射规则就是路由端口对应私有网络的主机 IP 地址。 假设 A 主机出站数据包源地址 192.168.0.20 是私有地址, 只能出现在私有网络,公网不认。

- 在它自己的公网 IP 上挑一个可用的 UDP 端口,例如 2.2.2.2:4242,

- 然后创建一个 NAT mapping:192.168.0.20:1234 <--> 2.2.2.2:4242,

- 然后将包发到公网,此时源地址变成了 2.2.2.2:4242 而不是原来的 192.168.0.20:1234。

因此服务端看到的是转换之后地址,接下来,每个能匹配到这条映射规则的包,都会被路由器改写 IP 和 端口。 反向数据的传输路径类似,路由器会执行相反的地址转换,将 2.2.2.2:4242 变回 192.168.0.20:1234。 对于私网主机来说,它根本感知不知道这正反两次变换过程。

NAT 技术的应用虽然缓解了 IPv4 地址稀缺问题,也增加了私网的安全功能,但它本身也引入了负面作用,破坏了现有的 IP 应用,开发 NAT 友好应用可以参考 RFC 3235 [NAT-APPL]。因而嵌入了早期的 Application Layer Gateways (ALGs) ,通过应用层网关,可以在应用层修改消息的地址。为了解决 ALG 和代理技术的可扩展性弱的问题,又研发了 Middlebox Communications (MIDCOM) 协议。MIDCOM 採用可信的第三方(MIDCOM Agent)对 Middlebox (NAT)进行控制,可以让应用(例如客户端、服务器、Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) 代理)控制 NAT 或者防火墙。但是 MIDCOM 要求更新现有的 NAT 和防火墙等网络设备,还有应用组件。MIDCOM 现存在的问题促使了 STUN 的出现,它不需要对 NAT 等网络设备做改动,并且可以解决任意层的 NAT 穿透。

到目前为止,不同网络间的互联通信还进行得挺好。但是,当互联网络中两个私有网络的主机需要直接互联时, 问题就来了。并且在 P2P 的网络模型中情况更糟糕:双方都需要主动和对方建连,但又不知道对方的公网地址, 只有当对方先说话之后,才能拿到它的地址信息。

如何破解以上死锁呢?这就轮到 STUN、ICE 和 TURN 等协议登场了。为了让双方在都未知对方地址的前提下 实现直接互联,需要使用一个“约会服务器”(Rendezvous Server),通过约会服务器的辅助实现的内网 穿透就称为打洞(Hole Punching)。

- RFC 3489 STUN - Simple Traversal of User Datagram Protocol (UDP) Through Network Address Translators (NATs)

- RFC 5389/8489 STUN: Session Traversal Utilities for NAT

- RFC 8445 ICE: A Protocol for Network Address Translator (NAT) Traversal

- RFC 5766/8665: Traversal Using Relays around NAT (TURN): Relay Extensions to Session Traversal Utilities for NAT (STUN)

ICE 不是一种协议,而是一套协议框架(Framework),它整合了 STUN 和 TURN。ICE 全称 Interactive Connectivity Establishment,互动式连接建立协议,它所提供的是一种框架,使各种 NAT 穿透技术可以实现统一。

TURN 如其名字所示,使用中继穿透 NAT:STUN 的中继扩展。简单的说,TURN 与 STUN 的共同点都是通过修改应用层中的私网地址数据实现 NAT 穿透,差异点是 TURN 通过两方通讯的“中间人”方式实现穿透。TURN 协议被设计为 ICE 的一部分,用于 NAT 穿透,虽然如此,它也可以在没有 ICE 的地方单独使用。

想了解更多新的 NAT 术语,可参考:

- RFC 5128 State of Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Communication across NATs

- RFC 4787 NAT Behavioral Requirements for Unicast UDP

- RFC 5382 NAT Behavioral Requirements for TCP

- RFC 5508 NAT Behavioral Requirements for ICMP

- RFC 5780 NAT Behavior Discovery Using STUN

P2P 通信解决方案一般包括下面两个步骤:

- 借助协调服务器(coordination server),尝试让通信双端建立连接,如果失败就向服务器反馈结果;

- 使用服务器中转(relay)作为后备支持,通信双方的数据经过 Server 转发给对方。

使用服务器中继的方式缺陷很明显,当链接的客户端变多之后,服务器就会成为性能瓶颈,完全体现不出 P2P 的去中心化的优势。但这种方法的好处是能保证成功,因此在实践中也常作为一种备选方案。

RFC 3489 定义 STUN 是一种基于 UDP 的轻量级 NAT 穿透解决方案。它允许通信双方的应用程序发现它们与公共互联网之间存在的 NAT 类型和防火墙。也可以让应用程序确定 NAT 分配给它们的公网 IP 地址和端口号。STUN 是一种 Client/Server 构架的协议,也是一种 Request/Response 协议,默认端口号是 3478。

一个 Classic STUN Client 脚本实现参考: https://github.com/evilpan/P2P-Over-MiddleBoxes-Demo/blob/master/stun/classic_stun_client.py

STUN 协议的判断流程图参考(来源维基百科):

RFC 3489 Classic STUN 文档中描述了 4 种基于 UDP 的经典 NAT 实现方法,为了表示一个确定的 IP:PORT 组合,使用端点(endpoint)这一术语表示,使用后缀数字 1、2、3 表示内网主机地址、NAT 映射地址、外网主机地址,并且内网(Inside local)向外网发包、外网(Outside global)向内网发包分别使用出站(Outgoing)、入站(Incoming)表示:

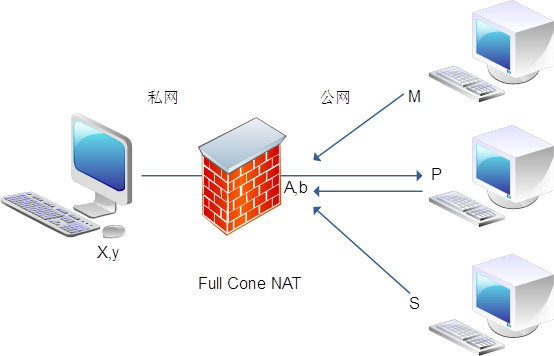

-

Full Cone NAT - 全锥 NAT:

同一个内网 Endpoint1 出站请求均被 NAT 映射成同一个外网 Endpoint2,并且任何外网主机都可以通过 Endpoint2 进行入站连接。由于对入站请求的来源无任何限制,因此这种方式虽然足够简单,但却不安全。

-

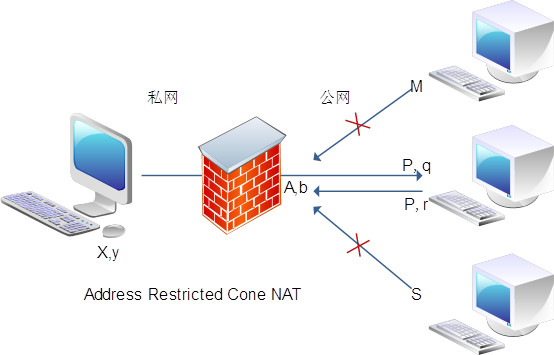

Restricted Cone NAT - 限锥 NAT:

同一个内网 Endpoint1 出站请求均被 NAT 映射成同一个外网 Endpoint2,但是只有 Endpoint1 曾经出站连接过的外部主机才能进行入站连接,只判断外网主机的 IP 地址。这意味着,NAT 设备只向内转发那些来自于当前已知的外部主机的数据包,从而保障了外部请求来源的安全性。

-

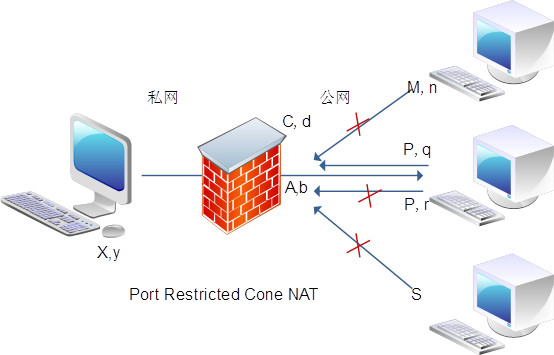

Port Restricted Cone NAT - 端口限锥 NAT:

与限锥 NAT 很相似,但是对端口作进一步限制。只有内网 Endpoint1 曾经出站连接过的外网主机 Endpoint3 (外网主机对应的 IP 和端口)。通过进一步约束 PORT,强化了对外部报文请求来源的限制,增强了安全性。

-

Symmetric NAT - 对称 NAT:

以上三种 Cone NAT,映射关系只和内网 Endpoint1 相关,只要 Endpoint1 不变,NAT 就都将其映射到同一个 Endpoint2。而对称 NAT 的映射关系不只与源 Endpoint1 相关,还与目的 Endpoint3 相关。也就是 Endpoint1 出站往目的 Endpoint3A,NAT 映射 Endpoint1 为 Endpoint2A;Endpoint1 发往目的 Endpoint3B 的请求,则被映射为 Endpoint2B。此外,只有经过内网主机出站连接的外网主机,才可以进行 UDP 入站连接。

文档中使用 Cone 这个词来形容 NAT 的实现方式,可能是考虑“穿透”这个动作的形象,演示图中的外网主机到 NAT 的连线就是一个锥形。通常,确定 NAT 工作于什么方式非常重要,不同方式决定了如何实现 NAT 穿透。

以上是 RFC 3489 Classic STUN 文档描述,最新的 RFC 8489 已经不使用这样的分类描述,并且 STUN 这个词的语义也发生了变化 Simple 变 Session,STUN 从穿透解决方案变成 NAT 穿透解决方案中的工具,应该参考最新的 RFC 5128 P2P 协议文档。

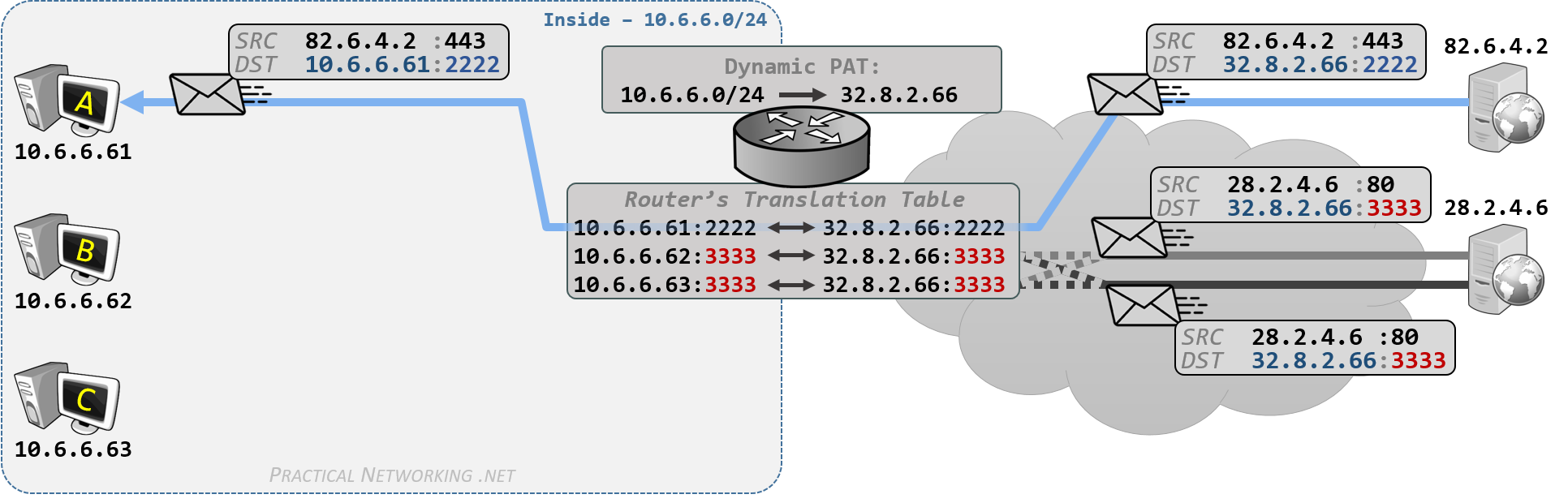

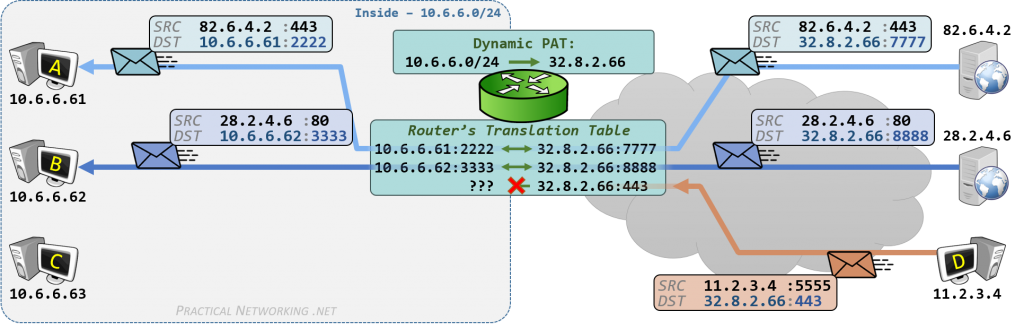

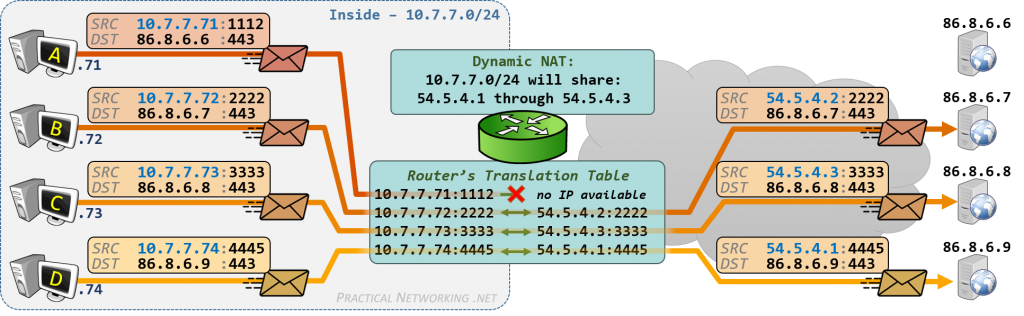

从网络设备的实现上来看,NAT 映射可以按 Static、Dynamic 与 NAT、PAT 进行组合。静态方式由网络管理员配置指定映射关系,动态方式由设备临时指定映射关系。然后组合 IP 地址映射,或者端口映射,就有 4 种组合。

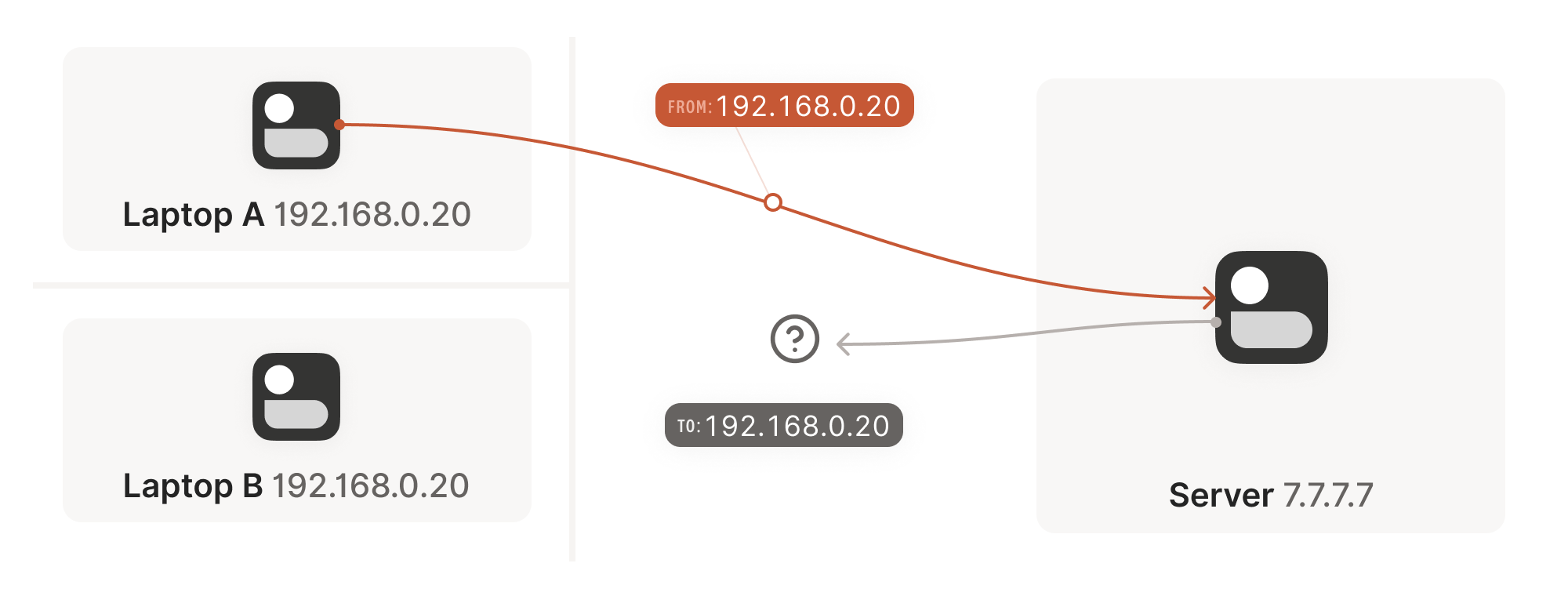

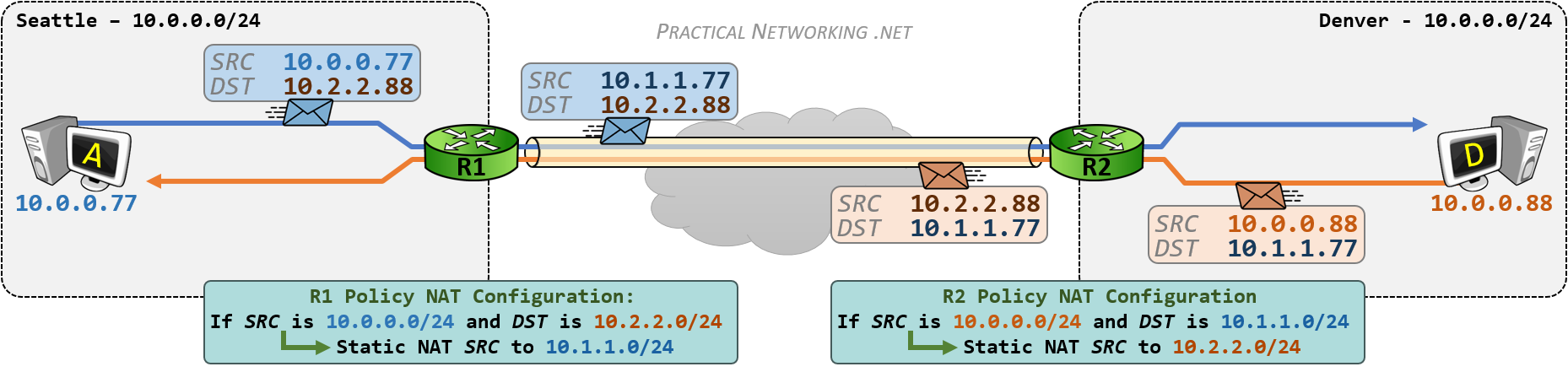

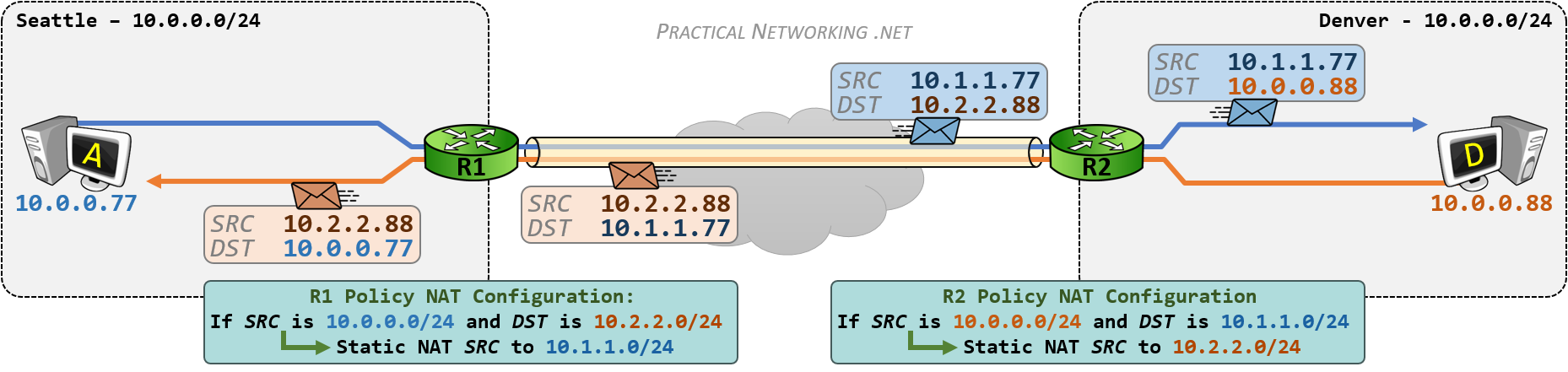

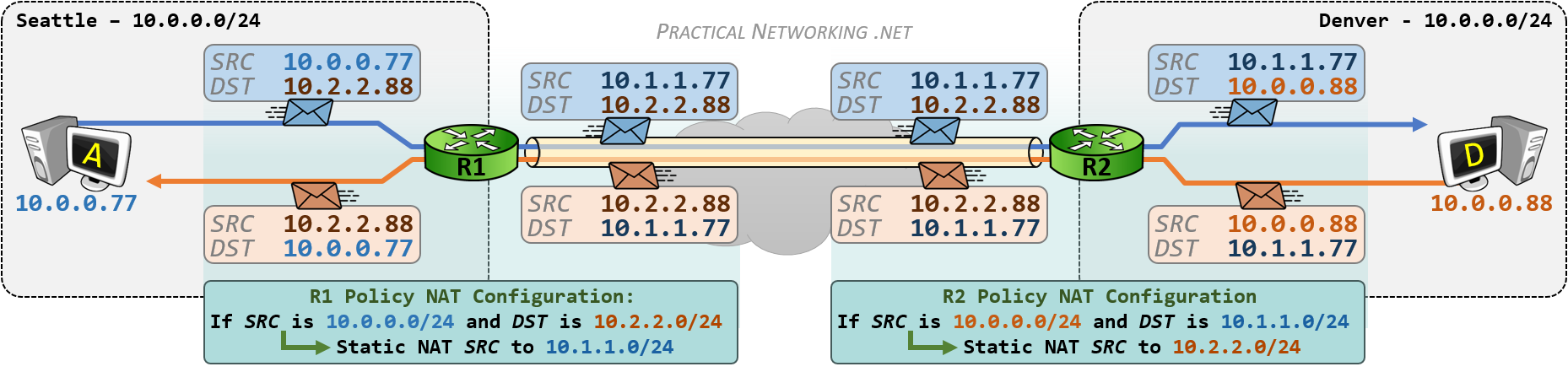

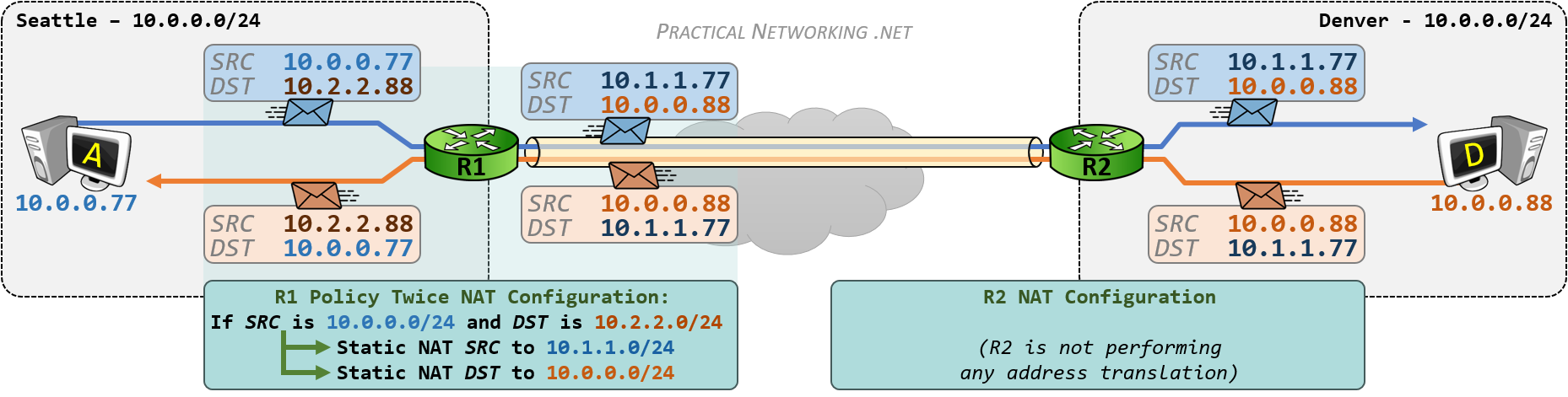

一般情况下,NAT 主要涉及修改出站数据包(outbound packet)的源 IP 地址的转换,将内部网络 IP 地址转换为外部网络的公共 IP 地址。或者修改入站数据包(inbound packet)的目标地址,将映射的公共 IP 地址修改为内网的 IP 地址。然而,有些情况需要对源地址和目标地址进行修改,这就需要 Twice NAT,相对于一般的 NAT 只修改单边的地址。

Twice NAT 的应用场景:

- 需要隐藏内网主机 IP 地址时,比如 VPN overlapping networks;

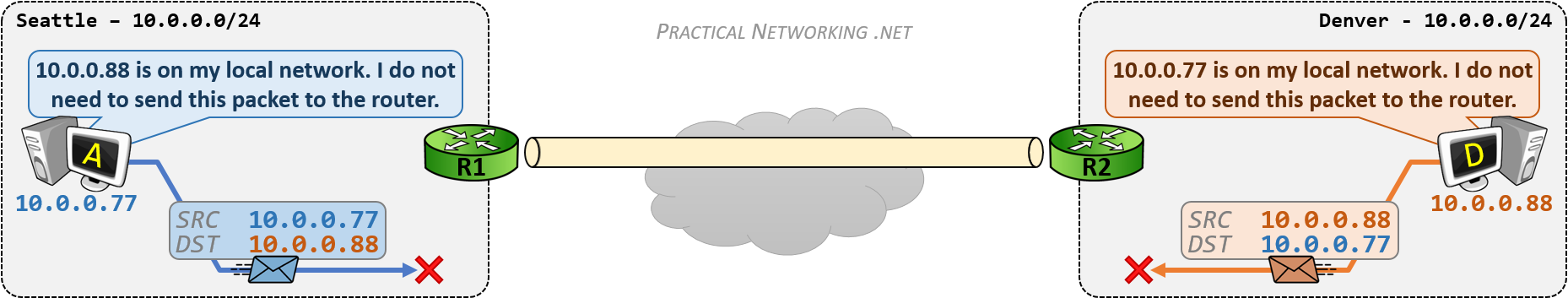

- 内部网络主机地址与外部网络上的主机地址重叠(overlapping),即不同网络中主机使用的 IP 地址相同;

- 多重地址转换:进行多次地址转换,将文经过多个转换节点,增加了网络的灵活性和扩展性。

- 跨网段通信:解决网段间的通信问题,使不同网段的主机能够互相访问。

下图演示了一次 DNS 请求过程中发生的 Twice NAT,原本 10.6.6.99 请求 DNS 服务器 8.8.8.8,但是经过 Twice NAT 映射后,数据包的源地址变为 NAT 设备的公网地址 32.8.2.55,目标地址变为另一台协同工作的 DNS 服务器 32.9.1.8:

内部网络主机地址与外部网络主机地址重叠的情况,NAT 会使用地址池中的临时地址替换 IP 包中的地址,解决内网地址与外网地址冲突问题。在数据包出站更换为临时地址,入站时再按映射关系修改回对应的真实地址。

Twice NAT is address translation where both source and destination IP addresses are modified due to addressing conflicts between two private realms. Two bi-directional NAT boxes connected together would essentially perform the same task, though a common address space that is not otherwise used by either private realm would be required.

Requirements for applications to work in the Twice NAT environment are the same as for Basic NAT. Addresses are mapped one to one.

参考 RFC 3235 NAT-Friendly Application Design Guidelines

RFC 5389 STUN 重新定义为 NAT 会话穿透工具,STUN - Session Traversal Utilities for NAT。STUN 本身不再是一种完整的 NAT 穿透解决方案,而是一种 NAT 穿透解决方案中的工具,也不再限定 UDP 是唯一支持的传输协议。因此将 RFC 3489 定义 STUN 称为经典 STUN(classic STUN)。

RFC 5128 P2P 协议文档更新了 NAT 的类型术语:

2. Terminology and Conventions Used ................................4

2.1. Endpoint ...................................................5

2.2. Endpoint Mapping ...........................................5

2.3. Endpoint-Independent Mapping ...............................5

2.4. Endpoint-Dependent Mapping .................................5

2.5. Endpoint-Independent Filtering .............................6

2.6. Endpoint-Dependent Filtering ...............................6

2.7. P2P Application ............................................7

2.8. NAT-Friendly P2P Application ...............................7

2.9. Endpoint-Independent Mapping NAT (EIM-NAT) .................7

2.10. Hairpinning ...............................................7

RFC 5128 P2P 协议文档 3. Techniques Used by P2P Applications to Traverse NATs 阐述了多种 NAT 穿透方法:

| Techniques Used to Traverse NATs | 说明 |

|---|---|

| Relaying | 服务器中继式穿透 |

| Connection Reversal | 逆向连接式穿透 |

| UDP Hole Punching | UDP 打洞穿透 |

| TCP Hole Punching | TCP 打洞穿透 |

| UDP Port Number Prediction | UDP 固定端口穿透 |

| TCP Port Number Prediction | TCP 固定端口穿透 |

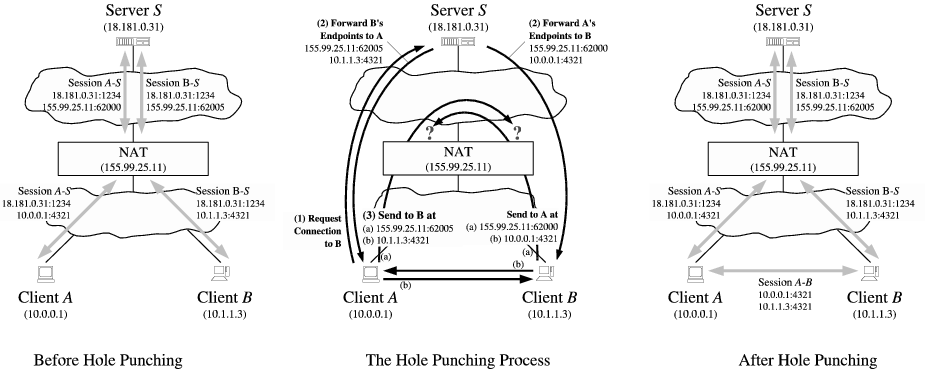

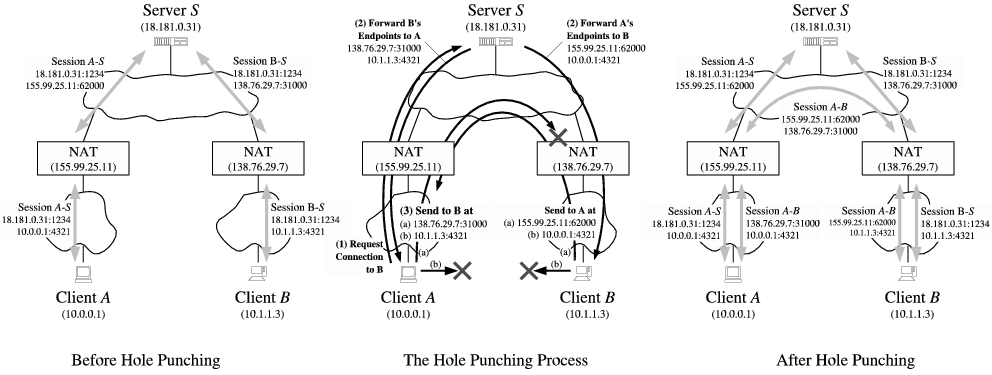

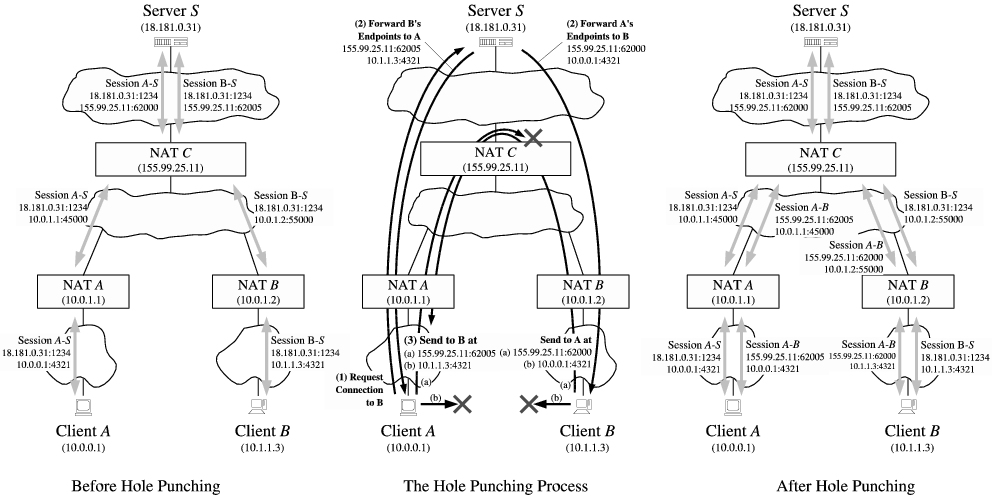

UDP 打洞穿透是应用最广泛的一种,也是 NAT 设备提供支持最好的一种,它又细分三各情形:

- 通信双端由不同 NAT 隔离(Peers behind Different NATs)

- 通信双端在同一 NAT 之内(Peers behind the Same NAT)

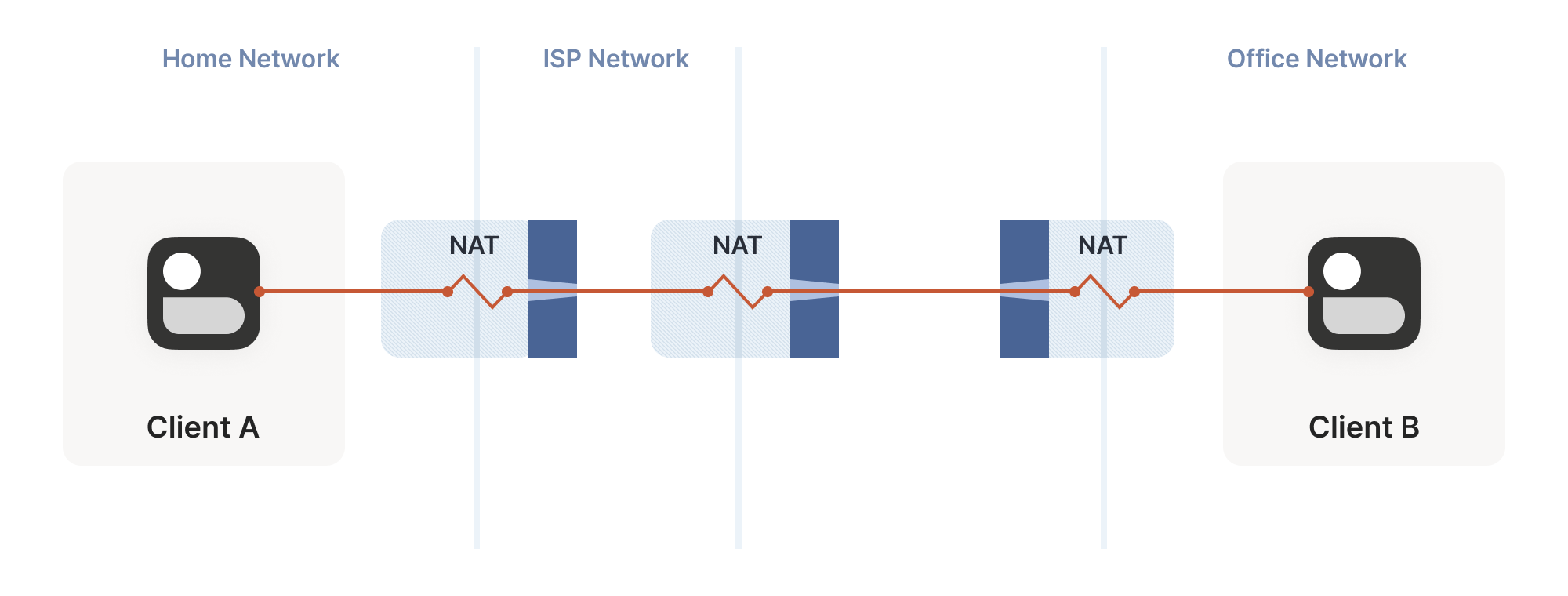

- 通信双端由多层 NAT 隔离(Peers Separated by Multiple NATs)

服务器中继式穿透(Relaying)是可靠的穿透方式,但效率低下。需要一台拥有公网 IP 的服务器来执行中继服务。假设以下网络结构,服务器 S

Registry, Discovery

Combined with Relay

Server S

192.0.2.128:20001

|

+----------------------------+----------------------------+

| ^ Registry/ ^ ^ Registry/ ^ |

| | Relay-Req Session(A-S) | | Relay-Req Session(B-S) | |

| | 192.0.2.128:20001 | | 192.0.2.128:20001 | |

| | 192.0.2.1:62000 | | 192.0.2.254:31000 | |

| |

+--------------+ +--------------+

| 192.0.2.1 | | 192.0.2.254 |

| | | |

| NAT A | | NAT B |

+--------------+ +--------------+

| |

| ^ Registry/ ^ ^ Registry/ ^ |

| | Relay-Req Session(A-S) | | Relay-Req Session(B-S) | |

| | 192.0.2.128:20001 | | 192.0.2.128:20001 | |

| | 10.0.0.1:1234 | | 10.1.1.3:1234 | |

| |

Client A Client B

10.0.0.1:1234 10.1.1.3:1234

Figure 1: Use of a Relay Server to communicate with peers

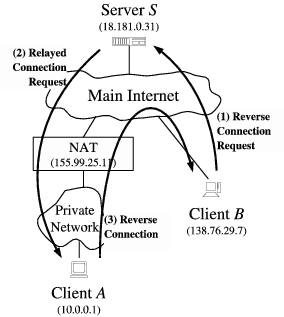

逆向连接式穿透(Connection Reversal)应用在通信双端只有一端在 NAT 背后。假设以下网络结构,A 端主机要连接 B 端主机等同一般 C/S 构架的客户端连接。但是私网内的 B 端不能直接向 A 发起连接,因为它没有公网 IP 地址。这就需要一台拥有公网 IP 的约会服务器(Rendezvous Server)进行协调,NAT 背后的主机向它注册端点(endpoint),其它主机通过它发现 NAT 背后的主机。

注意“连接”一词,TCP 协议是基于连接的通信协议,一切来自还没有建立连接的主机的数据包都会被丢弃。但是,“连接”作为一个日常用语,它也可以表示发送数据包尝试建立连接的过程。

假设 A 端连接 S 服务器时,NAT 为 A 10.0.0.1:1234 分配了一个公网映射地址 192.0.2.1:62000,服务器通过建立的连接登记这个 A 端点的地址。B 就可以通过 S 向 A 中继一个链接请求,从而实现“逆向“地建立 A->B 之间的点对点链接。

如果 A 端没有建立与 S 的连接,没有执行 Registry Session(B-S) 这个过程,此时 B 端连接 192.0.2.1:62000 依然会失败,因为来自 B 的 TCP SYN 握手请求到达 NAT A 的时候会被拒绝,NAT A 还没有建立与私网主机的映射关系,只允许出站链接。

Registry and Discovery

Server S

192.0.2.128:20001

|

+----------------------------+----------------------------+

| ^ Registry Session(A-S) ^ ^ Registry Session(B-S) ^ |

| | 192.0.2.128:20001 | | 192.0.2.128:20001 | |

| | 192.0.2.1:62000 | | 192.0.2.254:1234 | |

| |

| ^ P2P Session (A-B) ^ | P2P Session (B-A) | |

| | 192.0.2.254:1234 | | 192.0.2.1:62000 | |

| | 192.0.2.1:62000 | v 192.0.2.254:1234 v |

| |

+--------------+ |

| 192.0.2.1 | |

| | |

| NAT A | |

+--------------+ |

| |

| ^ Registry Session(A-S) ^ |

| | 192.0.2.128:20001 | |

| | 10.0.0.1:1234 | |

| |

| ^ P2P Session (A-B) ^ |

| | 192.0.2.254:1234 | |

| | 10.0.0.1:1234 | |

| |

Private Client A Public Client B

10.0.0.1:1234 192.0.2.254:1234

Figure 2: Connection reversal using Rendezvous server

UPD 打洞穿透基于 Endpoint-Independent Mapping NAT (EIM-NAT) 设备。

有不少公开的 STUN 服务器,ping 测试通过,可以直接使用:

stun.l.google.com:19302

stun.stunprotocol.org

stun.minisipserver.com

stun.zoiper.com

stun.voipbuster.com

stun.sipgate.net

stun.schlund.de

stun.voipstunt.com

stun.1und1.de

stun.gmx.net

stun.callwithus.com

stun.internetcalls.com

stun.voip.aebc.com

stun.internetcalls.com

stun.callwithus.com

stun.gmx.net

stun.1und1.de

stun.voxgratia.org

https://www.fortinet.com/resources/cyberglossary/network-address-translation

Network address translation (NAT) is a technique commonly used by internet service providers (ISPs) and organizations to enable multiple devices to share a single public IP address. By using NAT, devices on a private network can communicate with devices on a public network without the need for each device to have its own unique IP address.

NAT was originally intended as a short-term solution to alleviate the shortage of available IPv4 addresses. By sharing a single IP address among multiple computers on a local network, NAT conserves the limited number of publicly routable IPv4 addresses. NAT also provides a layer of security for private networks because it hides devices' actual IP addresses behind a single public IP address.

One of the most common problems that can occur when setting up a home or office network is an Internet Protocol (IP) address conflict. [IP addresses] are assigned to each device on a network, and no two devices can have the same IP address. If two devices on the same network carry the same IP address, connection issues will arise.

There are a few ways you can avoid IP address conflicts. One is through network address translation (NAT).

NAT is typically implemented on a router, a device that connects two networks. When a device on the private network sends data to a device on the public network, the router intercepts the data and replaces the source IP address with its own public IP address. The router then sends the data to the destination device.

When the destination device sends data back to the router, the router intercepts this data and replaces the public IP address with the original source IP address. The router then sends the data to the original source device. This process is transparent to the devices on both networks.

To help you better visualize how NAT works, here are a few network address translation examples:

- A router connects a private network to the internet: The router, configured to use NAT, translates the private IP addresses of devices on the network into public IP addresses. This enables internal devices to communicate with devices on the internet, while remaining hidden from public view.

- An organization has multiple office locations and wants to connect them all using a private network: NAT can be used to translate the IP addresses of devices on each network so they can communicate with one another as if they were on the same network. This allows the company to keep its internal network private and secure, while allowing employees at different locations to communicate with each other.

Network address translation offers multiple significant benefits:

- IP address conservation: By enabling multiple devices to share a single IP address, NAT helps conserve IP address space. This is especially important for organizations that have been assigned a limited number of IP addresses by their ISP.

- Improved security: NAT can provide a measure of security by hiding the internal network from the outside world. This can be useful for preventing attacks that target specific IP addresses or for preventing devices on the internal network from being accessed directly from the internet. NAT can also help prevent devices on the internal network from accessing malicious or unwanted websites.

- Better speed: NAT can improve communication speed by reducing the number of packets that need to be routed through the network. This is because NAT eliminates the need for each device on the internal network to have its own unique IP address.

- Flexibility: NAT can also be used to provide flexibility in network design, which is particularly useful for organizations that want to change their network configuration without changing their IP addresses. Organizations may want to change their network configuration to improve security or performance or to add new devices to the network.

- **Multi-homing:**NAT can be used to allow devices on a private network to connect to multiple public networks, a network configuration practice called multi-homing. This can be valuable for organizations that want to connect to multiple ISPs or that want to provide [failover] in case one of the ISPs goes down. Multi-homing with NAT provides connection redundancy and increases uptime by allowing traffic to be routed through multiple ISPs.

- Cost savings: NAT reduces the number of IP addresses an organization needs, which can save them money on IP address licenses and other associated costs.

- Easier network administration: NAT makes it easier to manage a network by reducing the number of IP addresses that need to be assigned. This benefits organizations with a large fleet of devices and those that want to reduce the amount of time and effort required to manage their networks.

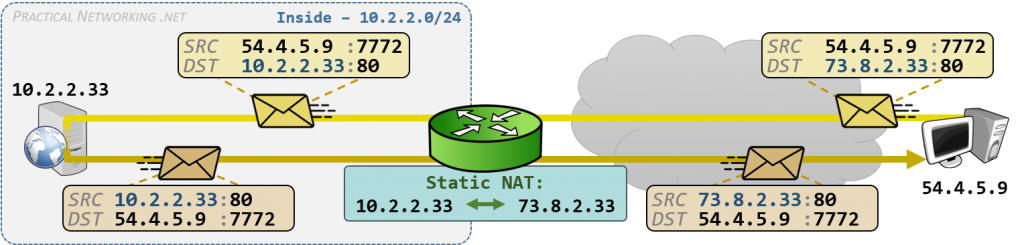

There are three network address translation types:

In static NAT, every internal IP address is mapped to a unique external IP address. This is one-to-one mapping. When outgoing traffic arrives at the router, the router replaces the destination IP address with the mapped global IP. When the return traffic comes back to the router, the router replaces the mapped global IP address with the source IP address.

Static NAT is mostly used in servers that need to be accessible from the internet, such as web servers and email servers.

In dynamic network address translation, internal IP addresses are mapped to a pool of external IP addresses. This is one-to-many mapping. When the outgoing traffic arrives at the router, the router replaces the destination IP address with a free global IP address from the pool. When the return traffic comes back to the router, the router replaces the mapped global IP address with the source IP address.

Dynamic NAT is mostly used in networks that need outbound internet connectivity.

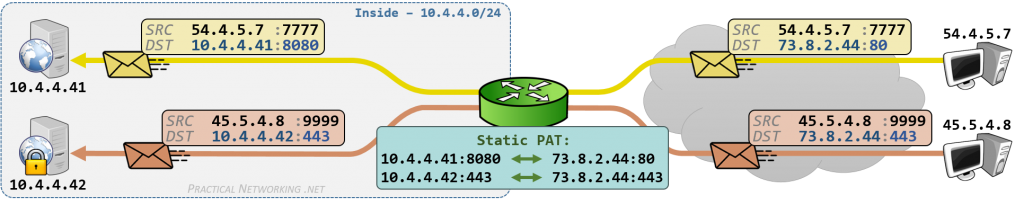

PAT is a type of dynamic NAT that maps multiple internal IP addresses to a single external IP address via port numbers. This is many-to-one mapping. When a computer connects to the internet, the router assigns it a port number that it then appends to the computer's internal IP address, in turn giving the computer a unique IP address. When a second computer connects to the internet, it gets the same external IP address but a different port number.

PAT is mostly used in home networks.

One way that NAT can help improve network security is by hiding internal IP addresses from external users. This makes it more difficult for attackers to target specific devices on the network.

Another way that NAT can improve security is by providing a level of traffic filtering. By controlling which internal IP addresses are mapped to external IP addresses, NAT can be used to block certain types of traffic from reaching internal systems. For example, an organization can use NAT to block all inbound traffic from a specific IP address or range of IP addresses that are known to be associated with malicious activity.

NAT can also help improve [network security] by making it easier to track and manage network traffic. By mapping internal IP addresses to a single external IP address, NAT can simplify the process of tracking and logging network activity. This can be helpful for identifying suspicious or unusual activity on the network.

The [Fortinet Security Fabric] offers a unified, integrated approach to security to enable organizations to better protect their networks from a variety of threats. It includes several built-in features, such as:

- A NAT engine for hiding internal IP addresses and providing a level of traffic filtering

- A traffic monitoring system to track and log network activity

- An intrusion prevention system for detecting and blocking suspicious traffic

Fortinet also boosts network security through the [FortiGate Next-Generation Firewall] (NGFW), which provides complete visibility and threat protection across your organization.

Network address translation (NAT) is a technique commonly used by internet service providers (ISPs) and organizations to enable multiple devices to share a single public IP address. By using NAT, devices on a private network can communicate with devices on a public network without the need for each device to have its own unique IP address.

The three main NAT types are static NAT, dynamic NAT, and port address translation (PAT).

When a device on the private network sends data to a device on the public network, the router intercepts the data and replaces the source IP address with its own public IP address. The router then sends the data to the destination device. When the destination device responds by sending data back to the router, the router intercepts this data and replaces the public IP address with the original source IP address. The router then sends the data to the original source device. This allows devices on a local network to communicate with devices on a public network without revealing their true IP addresses.

There are several benefits of using NAT. These include improved security, increased privacy, and improved network performance. NAT can also help conserve IP addresses by allowing multiple devices to share a single public IP address.

https://computer.howstuffworks.com/nat.htm

Network Address Translation helps improve security by reusing IP addresses. The NAT router translates traffic coming into and leaving the private network.

If you are reading this article, you are most likely connected to the Internet and viewing it at the HowStuffWorks Web site. There's a very good chance that you are using Network Address Translation (NAT) right now.

The Internet has grown larger than anyone ever imagined it could be. Although the exact size is unknown, the current estimate is that there are about 100 million hosts and more than 350 million users actively on the Internet. That is more than the entire population of the United States! In fact, the rate of growth has been such that the Internet is effectively doubling in size each year.

So what does the size of the Internet have to do with NAT? Everything! For a computer to communicate with other computers and [Web servers] on the Internet, it must have an IP address. An [IP address] (IP stands for Internet Protocol) is a unique 32-bit number that identifies the location of your computer on a network. Basically, it works like your street address -- as a way to find out exactly where you are and deliver information to you.

When IP addressing first came out, everyone thought that there were plenty of addresses to cover any need. Theoretically, you could have [4,294,967,296 unique addresses] (2^32). The actual number of available addresses is smaller (somewhere between 3.2 and 3.3 billion) because of the way that the addresses are separated into classes, and because some addresses are set aside for multicasting, testing or other special uses.

With the explosion of the Internet and the increase in [home networks] and business networks, the number of available IP addresses is simply not enough. The obvious solution is to redesign the address format to allow for more possible addresses. This is being developed (called IPv6), but will take several years to implement because it requires modification of the entire infrastructure of the Internet.

This is where NAT (RFC 1631) comes to the rescue. Network Address Translation allows a single device, such as a [router], to act as an agent between the Internet (or "public network") and a local (or "private") network. This means that only a single, unique IP address is required to represent an entire group of computers.

But the shortage of IP addresses is only one reason to use NAT. In this article, you will learn more about how NAT can benefit you. But first, let's take a closer look at NAT and exactly what it can do...

Contents

- What Does NAT Do?

- NAT Configuration

- Dynamic NAT and Overloading

- Stub Domains

- Security and Administration

- Multi-homing

NAT is like the receptionist in a large office. Let's say you have left instructions with the receptionist not to forward any calls to you unless you request it. Later on, you call a potential client and leave a message for that client to call you back. You tell the receptionist that you are expecting a call from this client and to put her through.

The client calls the main number to your office, which is the only number the client knows. When the client tells the receptionist that she is looking for you, the receptionist checks a lookup table that matches your name with your extension. The receptionist knows that you requested this call, and therefore forwards the caller to your extension.

Developed by Cisco, Network Address Translation is used by a device ([firewall], [router] or computer that sits between an internal network and the rest of the world. NAT has many forms and can work in several ways:

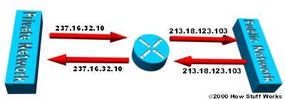

In static NAT, the computer with the IP address of 192.168.32.10 will always translate to 213.18.123.110.

- Static NAT - Mapping an unregistered IP address to a registered IP address on a one-to-one basis. Particularly useful when a device needs to be accessible from outside the network.

In dynamic NAT, the computer with the IP address 192.168.32.10 will translate to the first available address in the range from 213.18.123.100 to 213.18.123.150.

-

Dynamic NAT - Maps an unregistered IP address to a registered IP address from a group of registered IP addresses.

-

Overloading - A form of dynamic NAT that maps multiple unregistered IP addresses to a single registered IP address by using different ports. This is known also as PAT (Port Address Translation), single address NAT or port-level multiplexed NAT.

In overloading, each computer on the private network is translated to the same IP address (213.18.123.100), but with a different port number assignment.

- Overlapping - When the IP addresses used on your internal network are registered IP addresses in use on another network, the router must maintain a lookup table of these addresses so that it can intercept them and replace them with registered unique IP addresses. It is important to note that the NAT router must translate the "internal" addresses to registered unique addresses as well as translate the "external" registered addresses to addresses that are unique to the private network. This can be done either through static NAT or by using DNS and implementing dynamic NAT.

The internal IP range (237.16.32.xx) is also a registered range used by another network. Therefore, the router is translating the addresses to avoid a potential conflict with another network. It will also translate the registered global IP addresses back to the unregistered local IP addresses when information is sent to the internal network.

The internal network is usually a LAN (Local Area Network), commonly referred to as the stub domain. A stub domain is a LAN that uses IP addresses internally. Most of the network traffic in a stub domain is local, so it doesn't travel outside the internal network. A stub domain can include both registered and unregistered IP addresses. Of course, any computers that use unregistered IP addresses must use Network Address Translation to communicate with the rest of the world.

In the next section we'll look at the different ways NAT can be configured.

Thank You

Special thanks to Cisco for its support in creating this article.

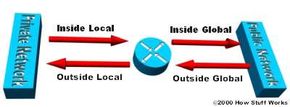

IP addresses have different designations based on whether they are on the private network (stub domain) or on the public network (Internet), and whether the traffic is incoming or outgoing.

NAT can be configured in various ways. In the example below, the NAT router is configured to translate unregistered (inside, local) IP addresses, that reside on the private (inside) network, to registered IP addresses. This happens whenever a device on the inside with an unregistered address needs to communicate with the public (outside) network.

-

An ISP assigns a range of IP addresses to your company. The assigned block of addresses are registered, unique IP addresses and are called inside global addresses. Unregistered, private IP addresses are split into two groups. One is a small group (outside local addresses) that will be used by the NAT routers. The other, much larger group, known as inside local addresses, will be used on the stub domain. The outside local addresses are used to translate the unique IP addresses, known as outside global addresses, of devices on the public network.

-

Most computers on the stub domain communicate with each other using the inside local addresses.

-

Some computers on the stub domain communicate a lot outside the network. These computers have inside global addresses, which means that they do not require translation.

-

When a computer on the stub domain that has an inside local address wants to communicate outside the network, the packet goes to one of the NAT routers.

-

The NAT router checks the routing table to see if it has an entry for the destination address. If it does, the NAT router then translates the packet and creates an entry for it in the address translation table. If the destination address is not in the routing table, the packet is dropped.

-

Using an inside global address, the router sends the packet on to its destination.

-

A computer on the public network sends a packet to the private network. The source address on the packet is an outside global address. The destination address is an inside global address.

-

The NAT router looks at the address translation table and determines that the destination address is in there, mapped to a computer on the stub domain.

-

The NAT router translates the inside global address of the packet to the inside local address, and sends it to the destination computer.

NAT overloading utilizes a feature of the [TCP/IP protocol stack], multiplexing, that allows a computer to maintain several concurrent connections with a remote computer (or computers) using different [TCP or UDP] ports. An IP packet has a header that contains the following information:

- Source Address - The IP address of the originating computer, such as 201.3.83.132

- Source Port - The TCP or UDP port number assigned by the originating computer for this packet, such as Port 1080

- Destination Address - The IP address of the receiving computer, such as 145.51.18.223

- Destination Port - The TCP or UDP port number that the originating computer is asking the receiving computer to open, such as Port 3021

The addresses specify the two machines at each end, while the port numbers ensure that the connection between the two computers has a unique identifier. The combination of these four numbers defines a single TCP/IP connection. Each port number uses 16 bits, which means that there are a possible 65,536 (216) values. Realistically, since different manufacturers map the ports in slightly different ways, you can expect to have about 4,000 ports available.

Here's how dynamic NAT works:

- An internal network (stub domain) has been set up with IP addresses that were not specifically allocated to that company by IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority), the global authority that hands out IP addresses. These addresses should be considered non-routable since they are not unique.

- The company sets up a NAT-enabled router. The router has a range of unique IP addresses given to the company by IANA.

- A computer on the stub domain attempts to connect to a computer outside the network, such as a Web server.

- The router receives the packet from the computer on the stub domain.

- The router saves the computer's non-routable IP address to an address translation table. The router replaces the sending computer's non-routable IP address with the first available IP address out of the range of unique IP addresses. The translation table now has a mapping of the computer's non-routable IP address matched with the one of the unique IP addresses.

- When a packet comes back from the destination computer, the router checks the destination address on the packet. It then looks in the address translation table to see which computer on the stub domain the packet belongs to. It changes the destination address to the one saved in the address translation table and sends it to that computer. If it doesn't find a match in the table, it drops the packet.

- The computer receives the packet from the router. The process repeats as long as the computer is communicating with the external system.

Here's how overloading works:

- An internal network (stub domain) has been set up with non-routable IP addresses that were not specifically allocated to that company by IANA.

- The company sets up a NAT-enabled router. The router has a unique IP address given to the company by IANA.

- A computer on the stub domain attempts to connect to a computer outside the network, such as a Web server.

- The router receives the packet from the computer on the stub domain.

- The router saves the computer's non-routable IP address and port number to an address translation table. The router replaces the sending computer's non-routable IP address with the router's IP address. The router replaces the sending computer's source port with the port number that matches where the router saved the sending computer's address information in the address translation table. The translation table now has a mapping of the computer's non-routable IP address and port number along with the router's IP address.

- When a packet comes back from the destination computer, the router checks the destination port on the packet. It then looks in the address translation table to see which computer on the stub domain the packet belongs to. It changes the destination address and destination port to the ones saved in the address translation table and sends it to that computer.

- The computer receives the packet from the router. The process repeats as long as the computer is communicating with the external system.

- Since the NAT router now has the computer's source address and source port saved to the address translation table, it will continue to use that same port number for the duration of the connection. A timer is reset each time the router accesses an entry in the table. If the entry is not accessed again before the timer expires, the entry is removed from the table.

In the next section we'll look at the organization of stub domains.

Look below to see how the computers on a stub domain might appear to external networks.

### Source Computer A

IP Address: 192.168.32.10

Computer Port: 400

NAT Router IP Address: 215.37.32.203

NAT Router Assigned Port Number: 1

### Source Computer B

IP Address: 192.168.32.13

Computer Port: 50

NAT Router IP Address: 215.37.32.203

NAT Router Assigned Port Number: 2

### Source Computer C

IP Address: 192.168.32.15

Computer Port: 3750

NAT Router IP Address: 215.37.32.203

NAT Router Assigned Port Number: 3

### Source Computer D

IP Address: 192.168.32.18

Computer Port: 206

NAT Router IP Address: 215.37.32.203

NAT Router Assigned Port Number: 4

As you can see, the NAT router stores the IP address and port number of each computer. It then replaces the IP address with its own registered IP address and the port number corresponding to the location, in the table, of the entry for that packet's source computer. So any external network sees the NAT router's IP address and the port number assigned by the router as the source-computer information on each packet.

You can still have some computers on the stub domain that use dedicated IP addresses. You can create an access list of IP addresses that tells the router which computers on the network require NAT. All other IP addresses will pass through untranslated.

The number of simultaneous translations that a router will support are determined mainly by the amount of DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory) it has. But since a typical entry in the address-translation table only takes about 160 bytes, a router with 4 MB of DRAM could theoretically process 26,214 simultaneous translations, which is more than enough for most applications.

IANA has set aside specific ranges of IP addresses for use as non-routable, internal network addresses. These addresses are considered unregistered (for more information check out RFC 1918: Address Allocation for Private Internets, which defines these address ranges). No company or agency can claim ownership of unregistered addresses or use them on public computers. Routers are designed to discard (instead of forward) unregistered addresses. What this means is that a packet from a computer with an unregistered address could reach a registered destination computer, but the reply would be discarded by the first router it came to.

There is a range for each of the three classes of IP addresses used for networking:

- Range 1: Class A - 10.0.0.0 through 10.255.255.255

- Range 2: Class B - 172.16.0.0 through 172.31.255.255

- Range 3: Class C - 192.168.0.0 through 192.168.255.255

Although each range is in a different class, your are not required to use any particular range for your internal network. It is a good practice, though, because it greatly diminishes the chance of an IP address conflict.

Static NAT (inbound mapping) allows a computer on the stub domain to maintain a specific address when communicating with devices outside the network.

Implementing dynamic NAT automatically creates a firewall between your internal network and outside networks, or between your internal network and the Internet. NAT only allows connections that originate inside the stub domain. Essentially, this means that a computer on an external network cannot connect to your computer unless your computer has initiated the contact. You can browse the Internet and connect to a site, and even download a file; but somebody else cannot latch onto your IP address and use it to connect to a port on your computer.

In specific circumstances, Static NAT, also called inbound mapping, allows external devices to initiate connections to computers on the stub domain. For instance, if you wish to go from an inside global address to a specific inside local address that is assigned to your Web server, Static NAT would enable the connection.

Some NAT routers provide for extensive filtering and traffic logging. Filtering allows your company to control what type of sites employees visit on the Web, preventing them from viewing questionable material. You can use traffic logging to create a log file of what sites are visited and generate various reports from it.

NAT is sometimes confused with proxy servers, but there are definite differences between them. NAT is transparent to the source and to destination computers. Neither one realizes that it is dealing with a third device. But a proxy server is not transparent. The source computer knows that it is making a request to the proxy server and must be configured to do so. The destination computer thinks that the proxy server IS the source computer, and deals with it directly. Also, proxy servers usually work at layer 4 (transport) of the OSI Reference Model or higher, while NAT is a layer 3 (network) protocol. Working at a higher layer makes proxy servers slower than NAT devices in most cases.

NAT operates at the Network layer (layer 3) of the OSI Reference Model -- this is the layer that routers work at.

A real benefit of NAT is apparent in network administration. For example, you can move your Web server or FTP server to another host computer without having to worry about broken links. Simply change the inbound mapping at the router to reflect the new host. You can also make changes to your internal network easily, because the only external IP address either belongs to the router or comes from a pool of global addresses.

NAT and DHCP (dynamic host configuration protocol ) are a natural fit. You can choose a range of unregistered IP addresses for your stub domain and have the DHCP server dole them out as necessary. It also makes it much easier to scale up your network as your needs grow. You don't have to request more IP addresses from IANA. Instead, you can just increase the range of available IP addresses configured in DHCP to immediately have room for additional computers on your network.

As businesses rely more and more on the Internet, having multiple points of connection to the Internet is fast becoming an integral part of their network strategy. Multiple connections, known as multi-homing, reduces the chance of a potentially catastrophic shutdown if one of the connections should fail.

In addition to maintaining a reliable connection, multi-homing allows a company to perform load-balancing by lowering the number of computers connecting to the Internet through any single connection. Distributing the load through multiple connections optimizes the performance and can significantly decrease wait times.

Multi-homed networks are often connected to several different ISPs (Internet Service Providers). Each ISP assigns an IP address (or range of IP addresses) to the company. Routers use BGP (Border Gateway Protocol), a part of the TCP/IP protocol suite, to route between networks using different protocols. In a multi-homed network, the router utilizes IBGP (Internal Border Gateway Protocol) on the stub domain side, and EBGP (External Border Gateway Protocol) to communicate with other routers.

Multi-homing really makes a difference if one of the connections to an ISP fails. As soon as the router assigned to connect to that ISP determines that the connection is down, it will reroute all data through one of the other routers.

NAT can be used to facilitate scalable routing for multi-homed, multi-provider connectivity. For more on multi-homing, see Cisco: Enabling Enterprise Multihoming.

For lots more information on NAT and related topics, check out the links on the next page.

A Network Address Translation or NAT is a mapping method of providing internet connection to local servers and hosts. In NAT, you take several local IPs and map them to one single global IP to transmit information across a routing device.

NAT only affects a little bit of your internet speed. It is barely noticeable if you’re using a reasonable router for translating your IPs.

With NAT enabled, it is easier to re-use your personal IP addresses with extra security. Moreover, NAT allows you to keep your external and internal IP addresses private and secure. You can also save the memory of your IP address by connecting several hosts via the internet using only a few external IPs.

NAT stands for Network Address Translation while PAT stands for Port Address Translation. As the names suggest, both NAT and PAT are used to translate private IPs into public IPs to save space and connect multiple devices. The difference is that PAT uses port numbers to map IP addresses whereas NAT doesn’t.

There are many forms of NAT. Static NAT maps an unregistered IP address to a registered IP address on a one-to-one basis; Dynamic NAT maps an unregistered IP address to a registered IP address from a group of registered IP addresses; Overloading maps multiple unregistered IP addresses to a single registered IP address by using different ports; Overlapping happens when a device on one network is assigned an IP address on the same subnet as another device on the internet or external network.

- How Web Servers Work

- How LAN Switches Work

- How Routers Work

- How Ethernet Works

- How Home Networking Works

- How OSI Works

- Network Address Translation FAQ

- Netsizer: Realtime Internet Growth

- Cisco: Network Address Translation

- NAT Technical Discussion

- Cisco: Configuring IP Addressing

- Cisco: NAT Overlapping

- Cisco: NAT Order of Operation

- IP Journal: The Trouble With NAT

- Cisco: Enabling Enterprise Multihoming

- RFC 1631: The IP Network Address Translator (NAT)

- RFC 1918: Address Allocation for Private Internets

Cite This!

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

Copy

Jeff Tyson "How Network Address Translation Works" 2 February 2001.

HowStuffWorks.com. https://computer.howstuffworks.com/nat.htm 18 March 2024

- https://tailscale.com/blog/how-nat-traversal-works

- NAT 穿透是如何工作的:技术原理及企业级实践 https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/450235047

August 21 2020 David Anderson

Contents

- Figuring out firewalls

- The nature of NATs

- NAT notes for nerds

- Integrating it all with ICE

- Concluding our connectivity chat

We covered a lot of ground in our post about How Tailscale Works. However, we glossed over how we can get through NATs (Network Address Translators) and connect your devices directly to each other, no matter what’s standing between them. Let’s talk about that now!

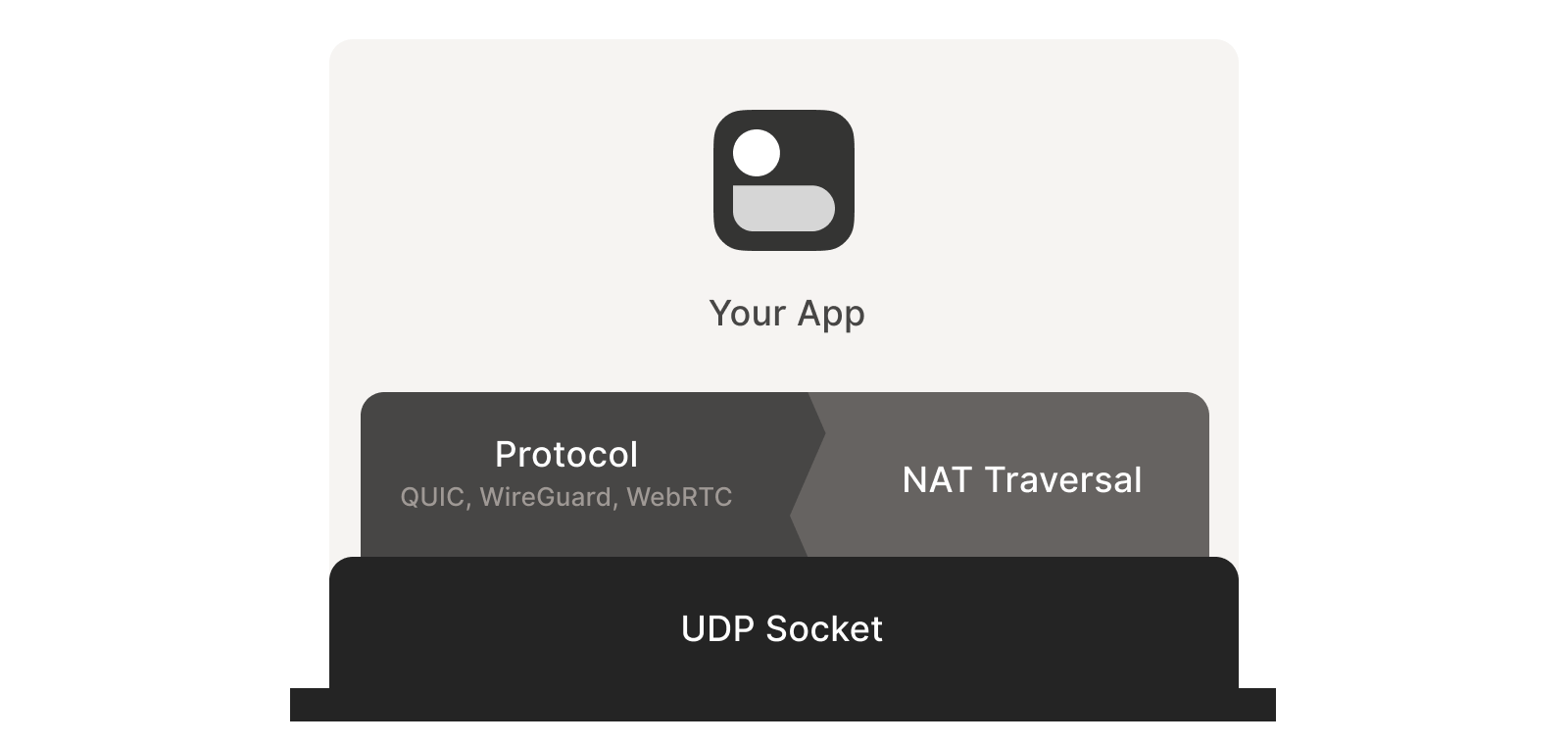

Let’s start with a simple problem: establishing a peer-to-peer connection between two machines. In Tailscale’s case, we want to set up a WireGuard® tunnel, but that doesn’t really matter. The techniques we use are widely applicable and the work of many people over decades. For example, WebRTC uses this bag of tricks to send peer-to-peer audio, video and data between web browsers. VoIP phones and some video games use similar techniques, though not always successfully.

We’ll be discussing these techniques generically, using Tailscale and others for examples where appropriate. Let’s say you’re making your own protocol and that you want NAT traversal. You need two things.

First, the protocol should be based on UDP. You can do NAT traversal with TCP, but it adds another layer of complexity to an already quite complex problem, and may even require kernel customizations depending on how deep you want to go. We’re going to focus on UDP for the rest of this article.

If you’re reaching for TCP because you want a stream-oriented connection when the NAT traversal is done, consider using QUIC instead. It builds on top of UDP, so we can focus on UDP for NAT traversal and still have a nice stream protocol at the end.

Second, you need direct control over the network socket that’s sending and receiving network packets. As a rule, you can’t take an existing network library and make it traverse NATs, because you have to send and receive extra packets that aren’t part of the “main” protocol you’re trying to speak. Some protocols tightly integrate the NAT traversal with the rest (e.g. WebRTC). But if you’re building your own, it’s helpful to think of NAT traversal as a separate entity that shares a socket with your main protocol. Both run in parallel, one enabling the other.

Direct socket access may be tough depending on your situation. One workaround is to run a local proxy. Your protocol speaks to this proxy, and the proxy does both NAT traversal and relaying of your packets to the peer. This layer of indirection lets you benefit from NAT traversal without altering your original program.

With prerequisites out of the way, let’s go through NAT traversal from first principles. Our goal is to get UDP packets flowing bidirectionally between two devices, so that our other protocol (WireGuard, QUIC, WebRTC, …) can do something cool. There are two obstacles to having this Just Work: stateful firewalls and NAT devices.

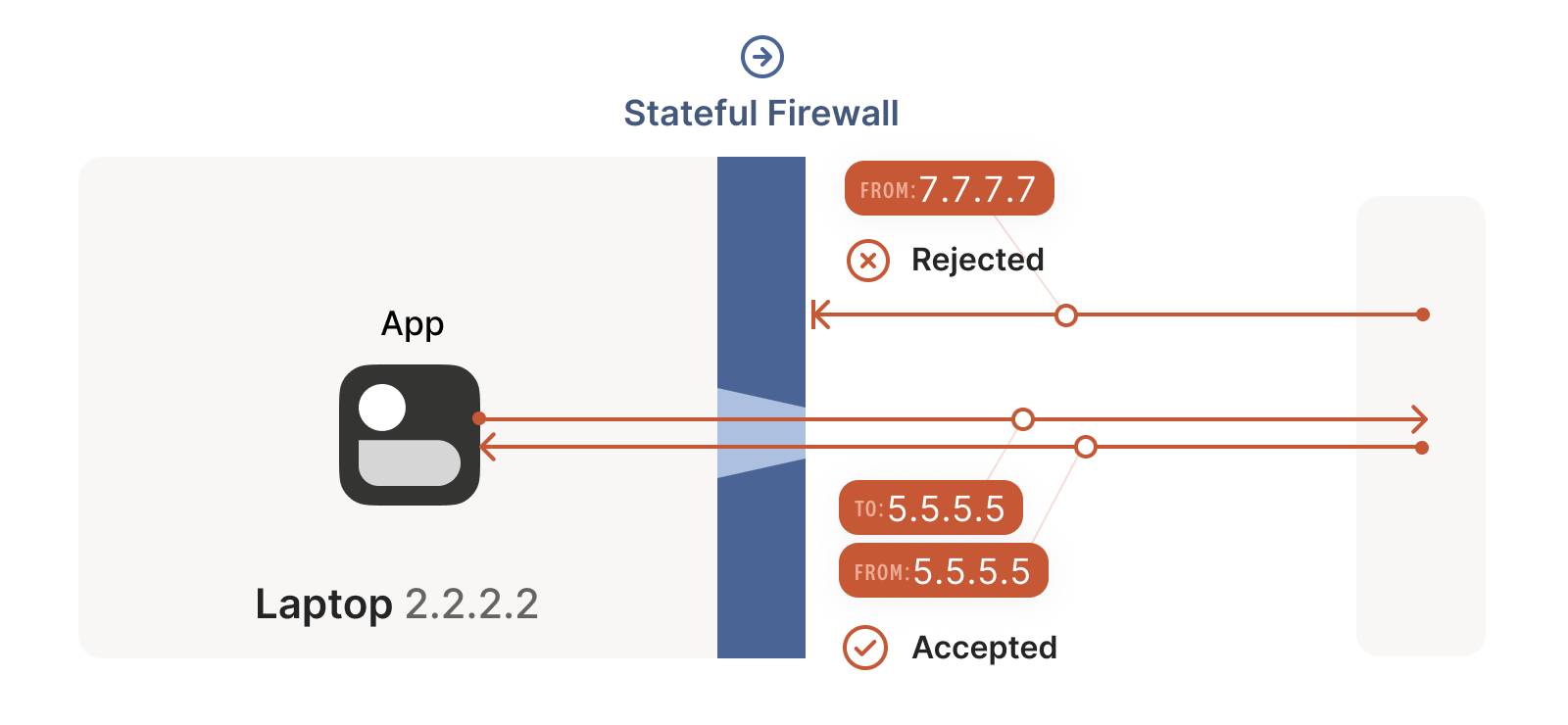

Stateful firewalls are the simpler of our two problems. In fact, most NAT devices include a stateful firewall, so we need to solve this subset before we can tackle NATs.

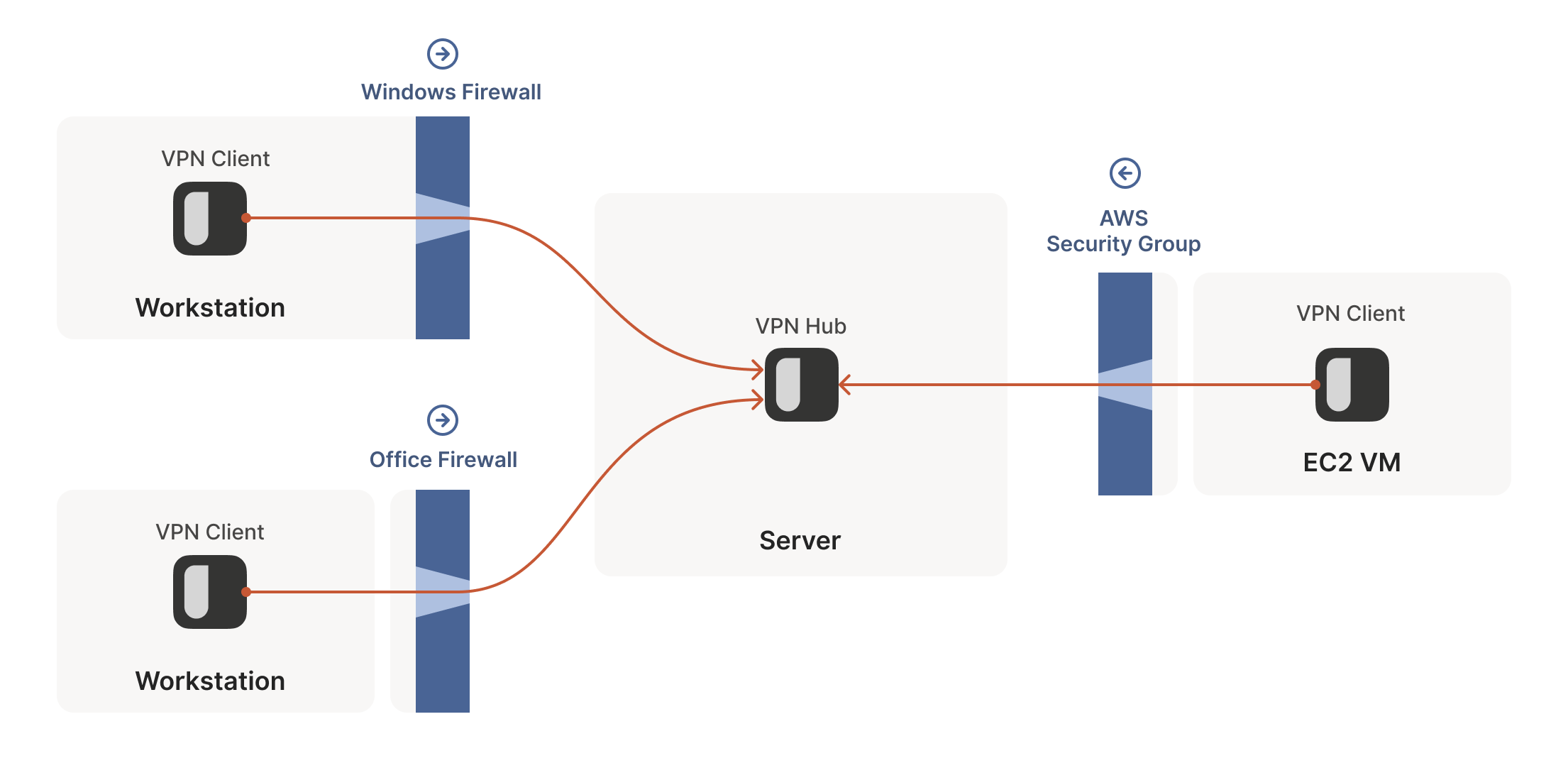

There are many incarnations to consider. Some you might recognize are the Windows Defender firewall, Ubuntu’s ufw (using iptables/nftables), BSD’s pf (also used by macOS) and AWS’s Security Groups. They’re all very configurable, but the most common configuration allows all “outbound” connections and blocks all “inbound” connections. There might be a few handpicked exceptions, such as allowing inbound SSH.

But connections and “direction” are a figment of the protocol designer’s imagination. On the wire, every connection ends up being bidirectional; it’s all individual packets flying back and forth. How does the firewall know what’s inbound and what’s outbound?

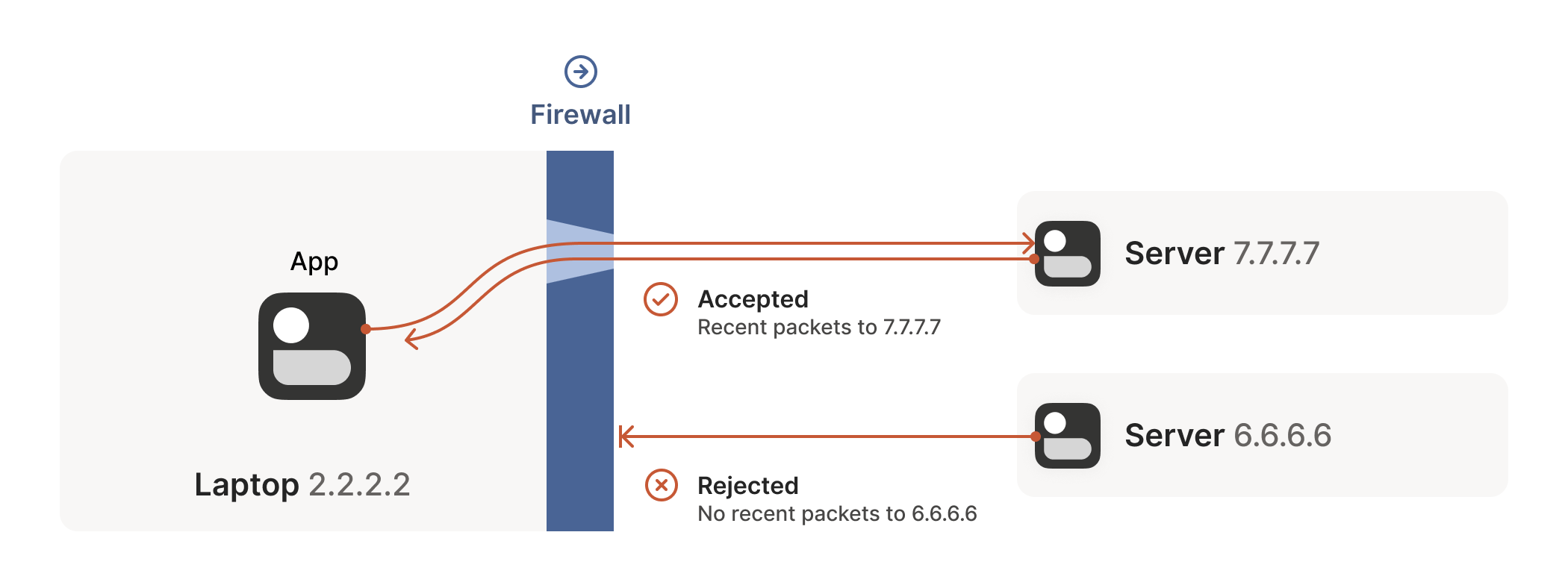

That’s where the stateful part comes in. Stateful firewalls remember what packets they’ve seen in the past and can use that knowledge when deciding what to do with new packets that show up.

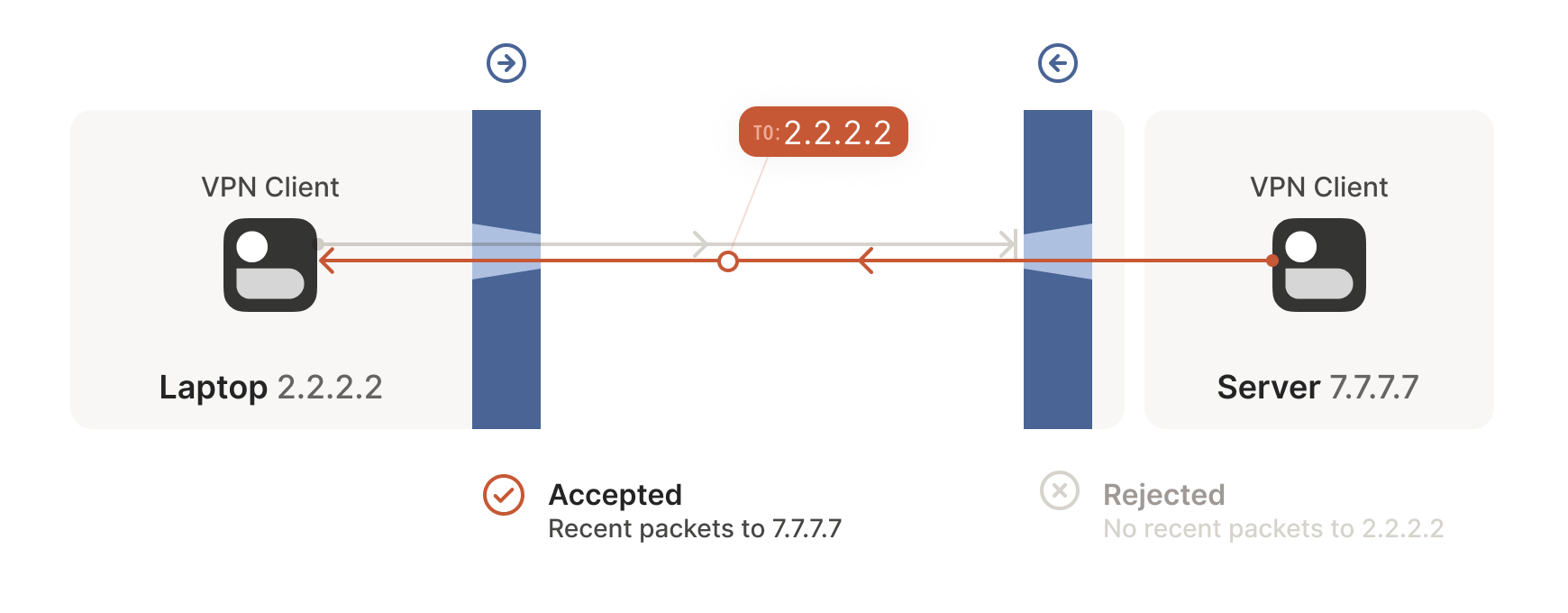

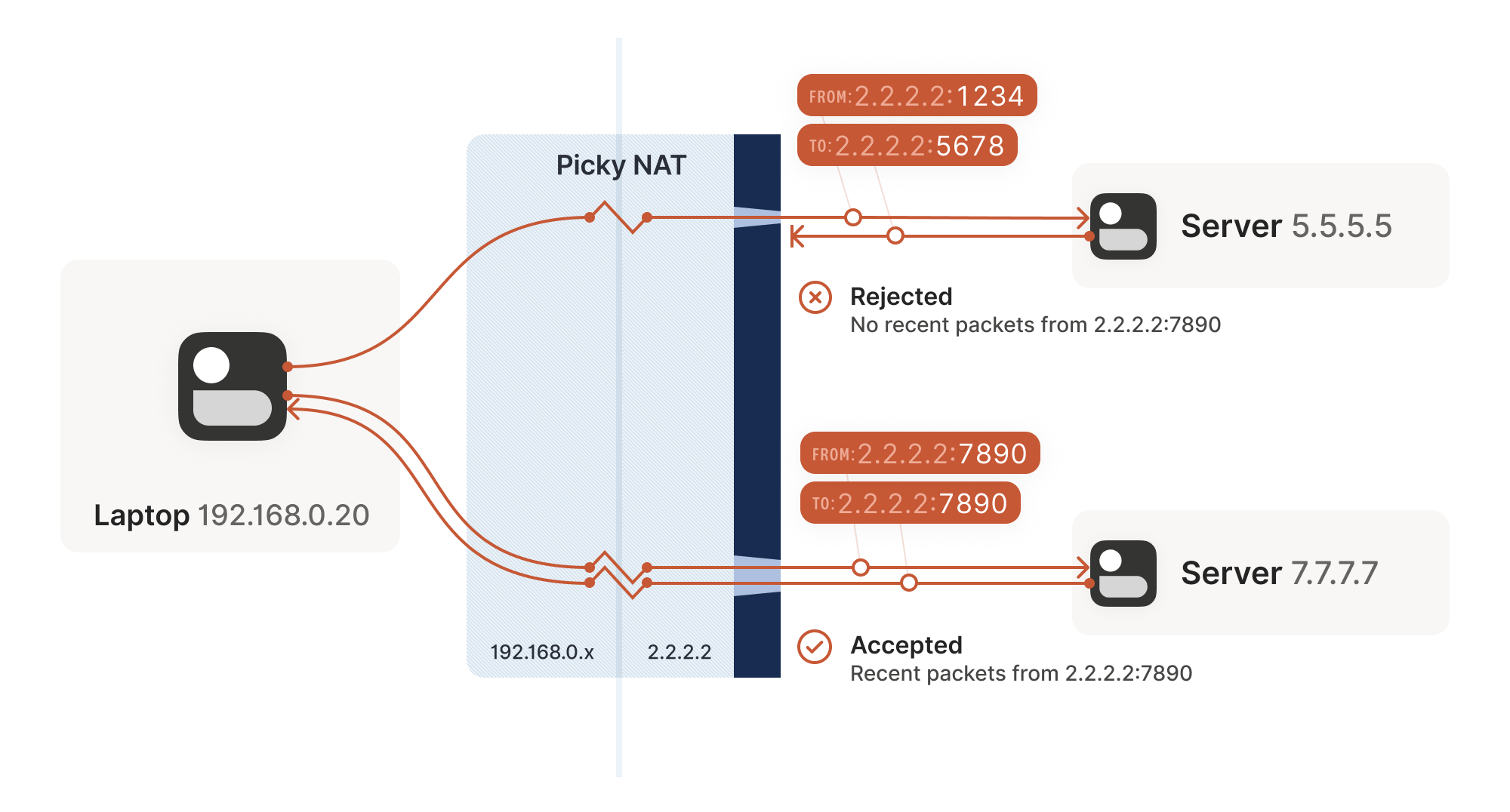

For UDP, the rule is very simple: the firewall allows an inbound UDP packet if it previously saw a matching outbound packet. For example, if our laptop firewall sees a UDP packet leaving the laptop from 2.2.2.2:1234 to 7.7.7.7:5678, it’ll make a note that incoming packets from 7.7.7.7:5678 to 2.2.2.2:1234 are also fine. The trusted side of the world clearly intended to communicate with 7.7.7.7:5678, so we should let them talk back.

(As an aside, some very relaxed firewalls might allow traffic from anywhere back to 2.2.2.2:1234 once 2.2.2.2:1234 has communicated with anyone. Such firewalls make our traversal job easier, but are increasingly rare.)

This rule for UDP traffic is only a minor problem for us, as long as all the firewalls on the path are “facing” the same way. That’s usually the case when you’re communicating with a server on the internet. Our only constraint is that the machine that’s behind the firewall must be the one initiating all connections. Nothing can talk to it, unless it talks first.

This is fine, but not very interesting: we’ve reinvented client/server communication, where the server makes itself easily reachable to clients. In the VPN world, this leads to a hub-and-spoke topology: the hub has no firewalls blocking access to it and the firewalled spokes connect to the hub.

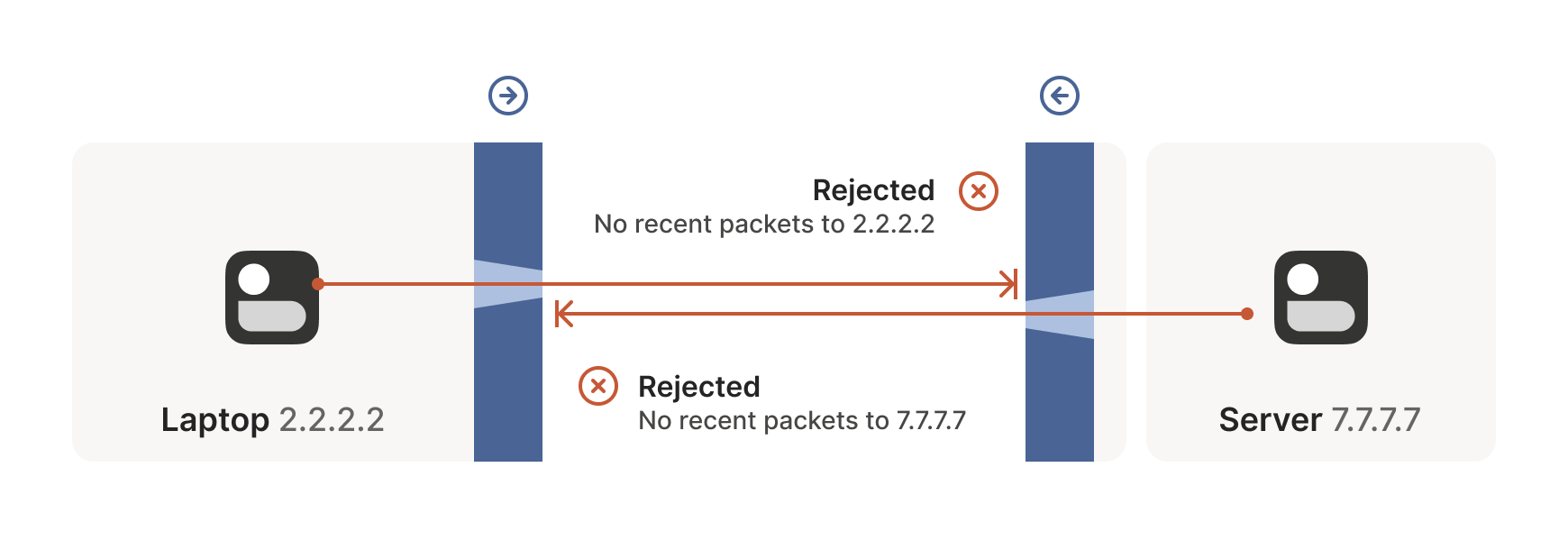

The problems start when two of our “clients” want to talk directly. Now the firewalls are facing each other. According to the rule we established above, this means both sides must go first, but also that neither can go first, because the other side has to go first!

How do we get around this? One way would be to require users to reconfigure one or both of the firewalls to “open a port” and allow the other machine’s traffic. This is not very user friendly. It also doesn’t scale to mesh networks like Tailscale, in which we expect the peers to be moving around the internet with some regularity. And, of course, in many cases you don’t have control over the firewalls: you can’t reconfigure the router in your favorite coffee shop, or at the airport. (At least, hopefully not!)

We need another option. One that doesn’t involve reconfiguring firewalls.

The trick is to carefully read the rule we established for our stateful firewalls. For UDP, the rule is: packets must flow out before packets can flow back in.

However, nothing says the packets must be related to each other beyond the IPs and ports lining up correctly. As long as some packet flowed outwards with the right source and destination, any packet that looks like a response will be allowed back in, even if the other side never received your packet!

So, to traverse these multiple stateful firewalls, we need to share some information to get underway: the peers have to know in advance the ip:port their counterpart is using. One approach is to statically configure each peer by hand, but this approach doesn’t scale very far. To move beyond that, we built a coordination server to keep the ip:port information synchronized in a flexible, secure manner.

Then, the peers start sending UDP packets to each other. They must expect some of these packets to get lost, so they can’t carry any precious information unless you’re prepared to retransmit them. This is generally true of UDP, but especially true here. We’re going to lose some packets in this process.

Our laptop and workstation are now listening on fixed ports, so that they both know exactly what ip:port to talk to. Let’s take a look at what happens.

The laptop’s first packet, from 2.2.2.2:1234 to 7.7.7.7:5678, goes through the Windows Defender firewall and out to the internet. The corporate firewall on the other end blocks the packet, since it has no record of 7.7.7.7:5678 ever talking to 2.2.2.2:1234. However, Windows Defender now remembers that it should expect and allow responses from 7.7.7.7:5678 to 2.2.2.2:1234.

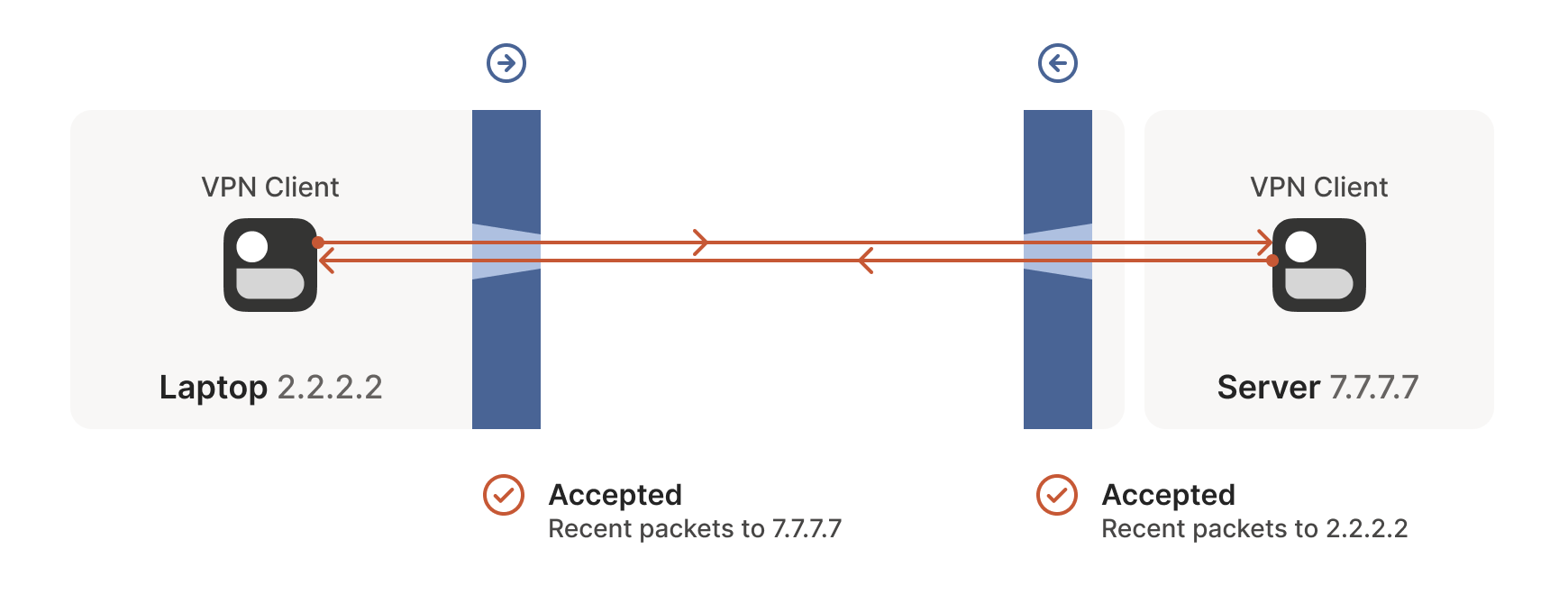

Next, the workstation’s first packet from 7.7.7.7:5678 to 2.2.2.2:1234 goes through the corporate firewall and across the internet. When it arrives at the laptop, Windows Defender thinks “ah, a response to that outbound request I saw”, and lets the packet through! Additionally, the corporate firewall now remembers that it should expect responses from 2.2.2.2:1234 to 7.7.7.7:5678, and that those packets are also okay.

Encouraged by the receipt of a packet from the workstation, the laptop sends another packet back. It goes through the Windows Defender firewall, through the corporate firewall (because it’s a “response” to a previously sent packet), and arrives at the workstation.

Success! We’ve established two-way communication through a pair of firewalls that, at first glance, would have prevented it.

It’s not always so easy. We’re relying on some indirect influence over third-party systems, which requires careful handling. What do we need to keep in mind when managing firewall-traversing connections?

Both endpoints must attempt communication at roughly the same time, so that all the intermediate firewalls open up while both peers are still around. One approach is to have the peers retry continuously, but this is wasteful. Wouldn’t it be better if both peers knew to start establishing a connection at the same time?

This may sound a little recursive: to communicate, first you need to be able to communicate. However, this preexisting “side channel” doesn’t need to be very fancy: it can have a few seconds of latency, and only needs to deliver a few thousand bytes in total, so a tiny VM can easily be a matchmaker for thousands of machines.

In the distant past, I used XMPP chat messages as the side channel, with great results. As another example, WebRTC requires you to come up with your own “signalling channel” (a name that reveals WebRTC’s IP telephony ancestry), and plug it into the WebRTC APIs. In Tailscale, our coordination server and fleet of DERP (Detour Encrypted Routing Protocol) servers act as our side channel.

Stateful firewalls have limited memory, meaning that we need periodic communication to keep connections alive. If no packets are seen for a while (a common value for UDP is 30 seconds), the firewall forgets about the session, and we have to start over. To avoid this, we use a timer and must either send packets regularly to reset the timers, or have some out-of-band way of restarting the connection on demand.

On the plus side, one thing we don’t need to worry about is exactly how many firewalls exist between our two peers. As long as they are stateful and allow outbound connections, the simultaneous transmission technique will get through any number of layers. That’s really nice, because it means we get to implement the logic once, and it’ll work everywhere.

…Right?

Well, not quite. For this to work, our peers need to know in advance what ip:port to use for their counterparts. This is where NATs come into play, and ruin our fun.

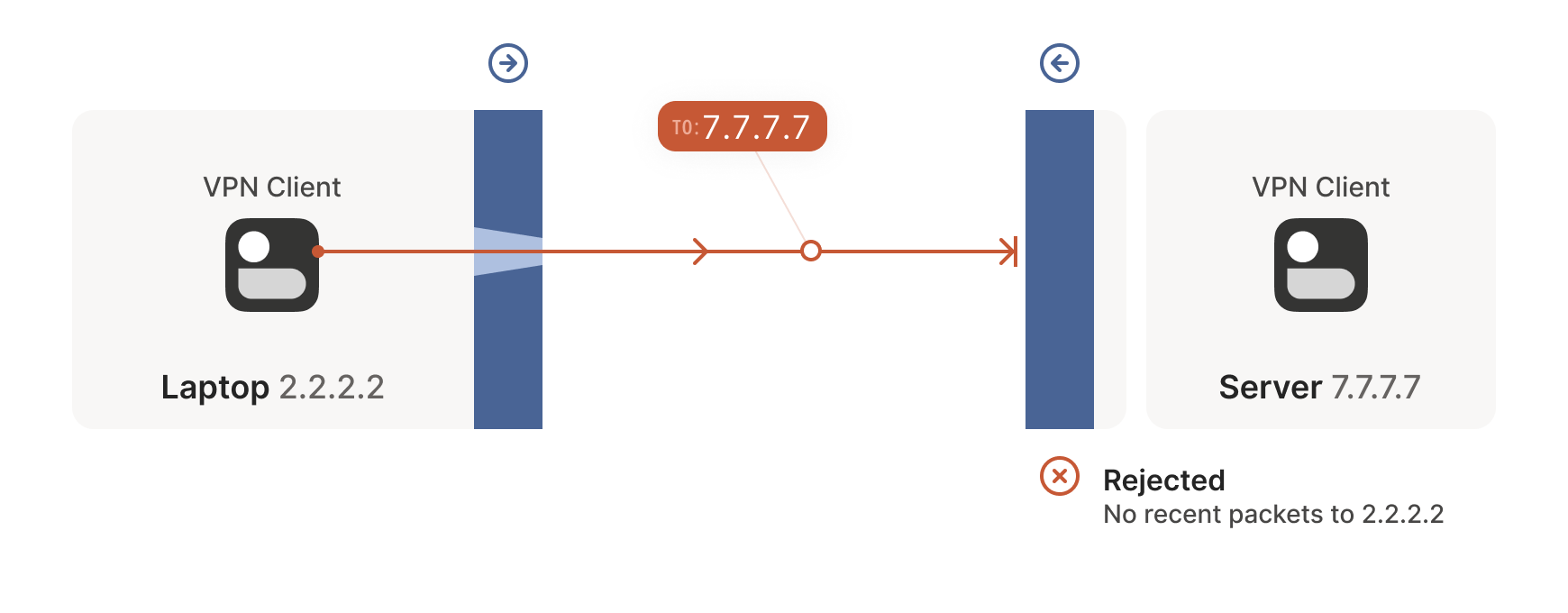

We can think of NAT (Network Address Translator) devices as stateful firewalls with one more really annoying feature: in addition to all the stateful firewalling stuff, they also alter packets as they go through.

A NAT device is anything that does any kind of Network Address Translation, i.e. altering the source or destination IP address or port. However, when talking about connectivity problems and NAT traversal, all the problems come from Source NAT, or SNAT for short. As you might expect, there is also DNAT (Destination NAT), and it’s very useful but not relevant to NAT traversal.

The most common use of SNAT is to connect many devices to the internet, using fewer IP addresses than the number of devices. In the case of consumer-grade routers, we map all devices onto a single public-facing IP address. This is desirable because it turns out that there are way more devices in the world that want internet access, than IP addresses to give them (at least in IPv4 — we’ll come to IPv6 in a little bit). NATs let us have many devices sharing a single IP address, so despite the global shortage of IPv4 addresses, we can scale the internet further with the addresses at hand.

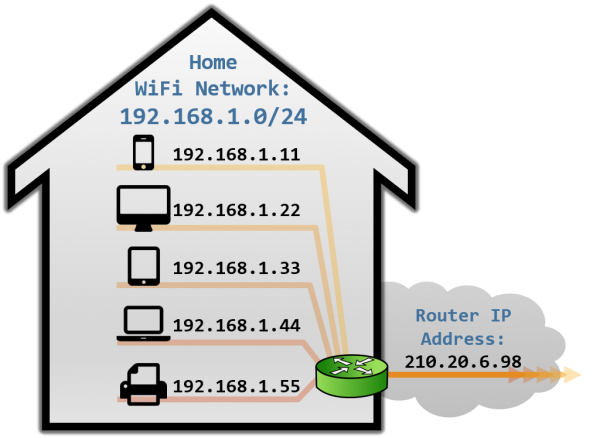

Let’s look at what happens when your laptop is connected to your home Wi-Fi and talks to a server on the internet.

Your laptop sends UDP packets from 192.168.0.20:1234 to 7.7.7.7:5678. This is exactly the same as if the laptop had a public IP. But that won’t work on the internet: 192.168.0.20 is a private IP address, which appears on many different peoples’ private networks. The internet won’t know how to get responses back to us.

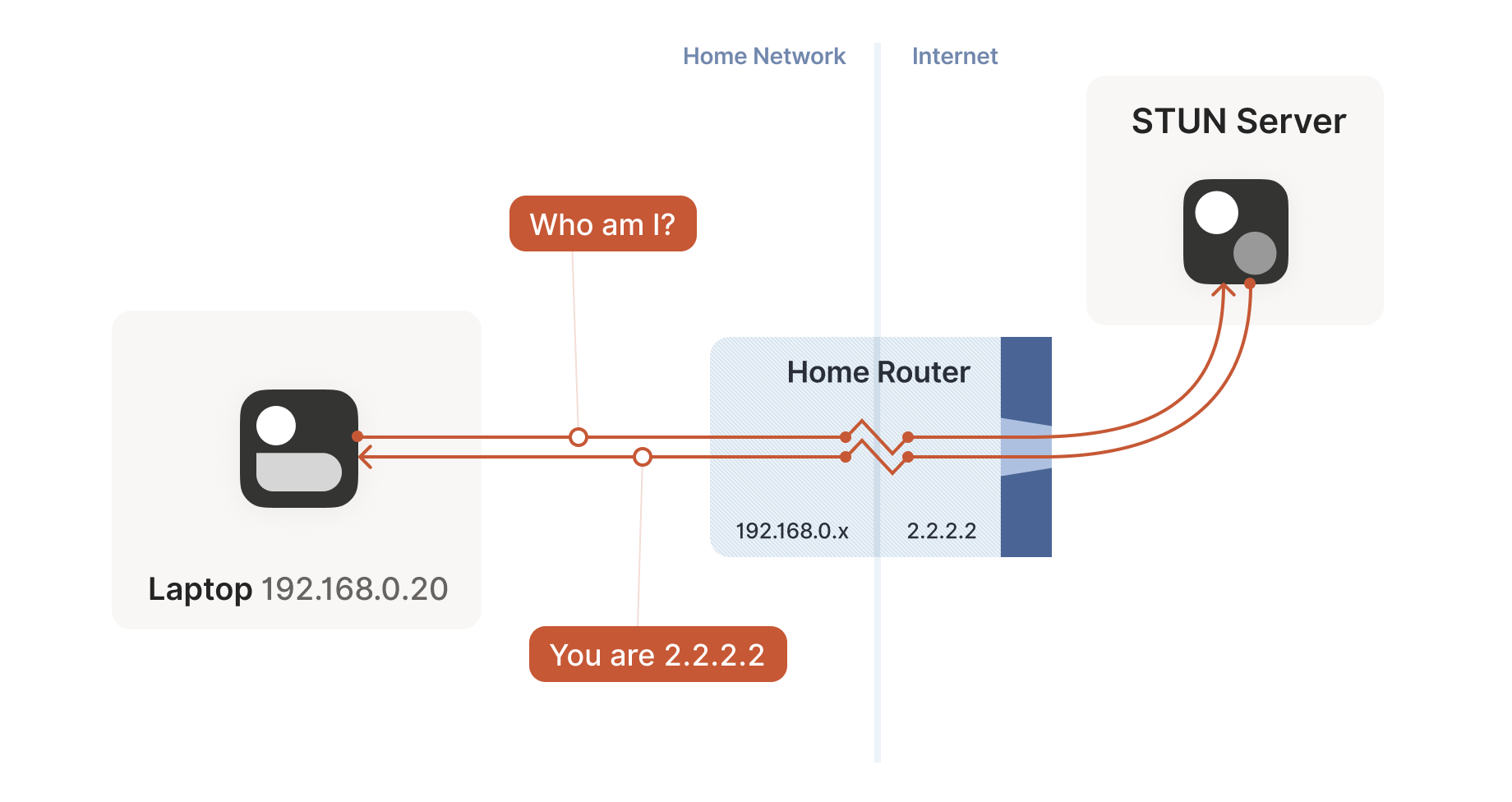

Enter the home router. The laptop’s packets flow through the home router on their way to the internet, and the router sees that this is a new session that it’s never seen before.

It knows that 192.168.0.20 won’t fly on the internet, but it can work around that: it picks some unused UDP port on its own public IP address — we’ll use 2.2.2.2:4242 — and creates a NAT mapping that establishes an equivalence: 192.168.0.20:1234 on the LAN side is the same as 2.2.2.2:4242 on the internet side.

From now on, whenever it sees packets that match that mapping, it will rewrite the IPs and ports in the packet appropriately.

Resuming our packet’s journey: the home router applies the NAT mapping it just created, and sends the packet onwards to the internet. Only now, the packet is from 2.2.2.2:4242, not 192.168.0.20:1234. It goes on to the server, which is none the wiser. It’s communicating with 2.2.2.2:4242, like in our previous examples sans NAT.

Responses from the server flow back the other way as you’d expect, with the home router rewriting 2.2.2.2:4242 back to 192.168.0.20:1234. The laptop is also none the wiser, from its perspective the internet magically figured out what to do with its private IP address.

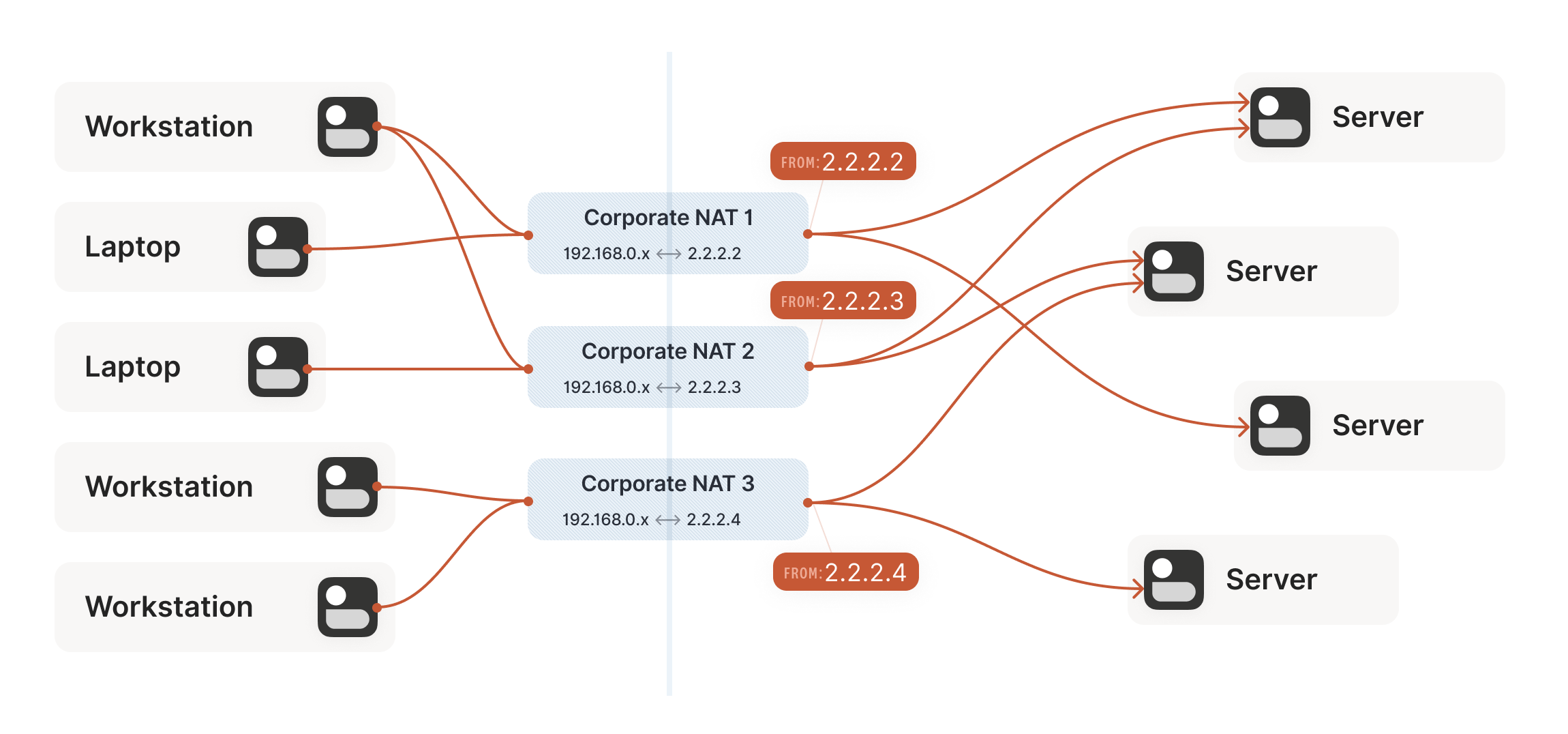

Our example here was with a home router, but the same principle applies on corporate networks. The usual difference there is that the NAT layer consists of multiple machines (for high availability or capacity reasons), and they can have more than one public IP address, so that they have more public ip:port combinations to choose from and can sustain more active clients at once.

Multiple NATs on a single layer allow for higher availability or capacity, but function the same as a single NAT.

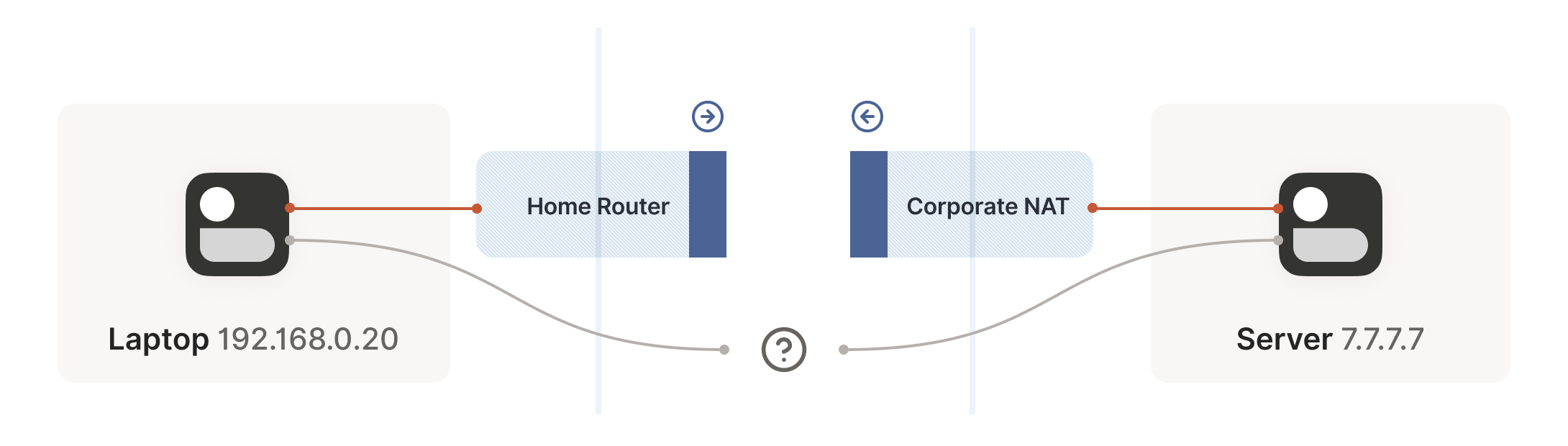

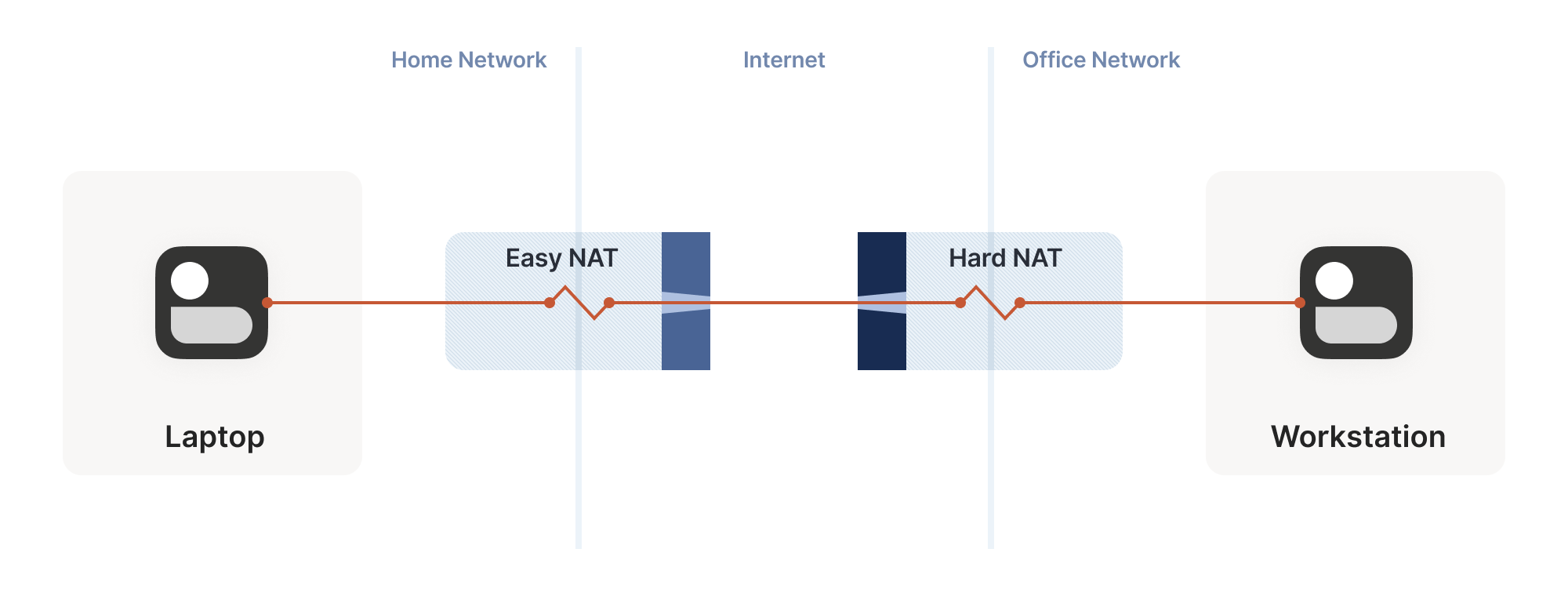

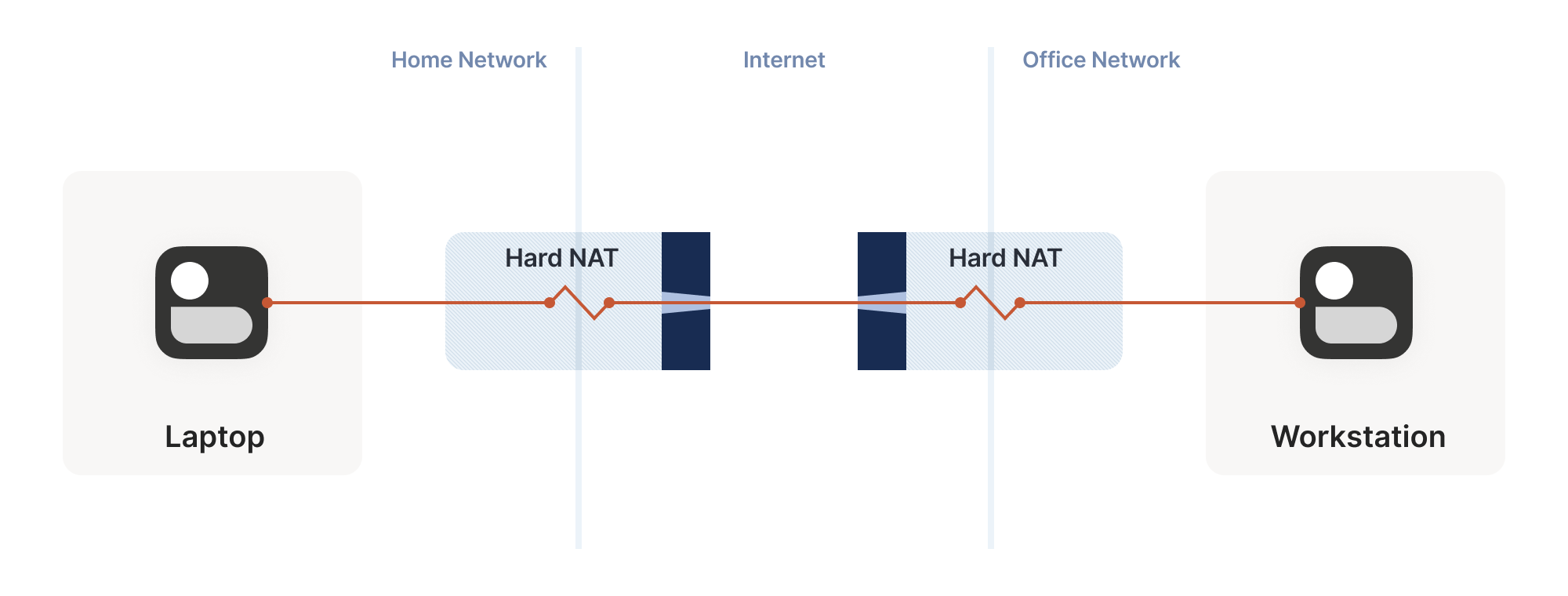

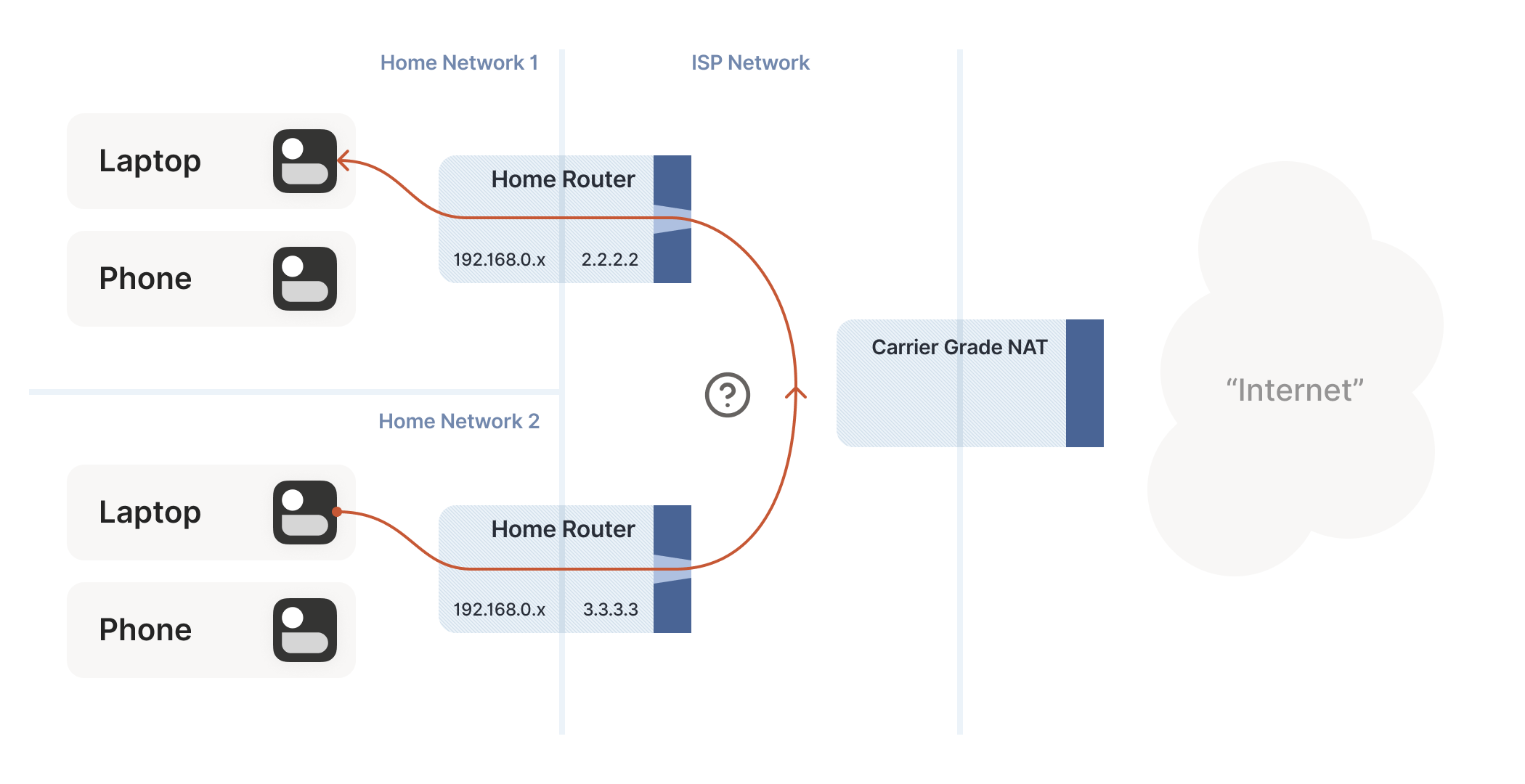

We now have a problem that looks like our earlier scenario with the stateful firewalls, but with NAT devices:

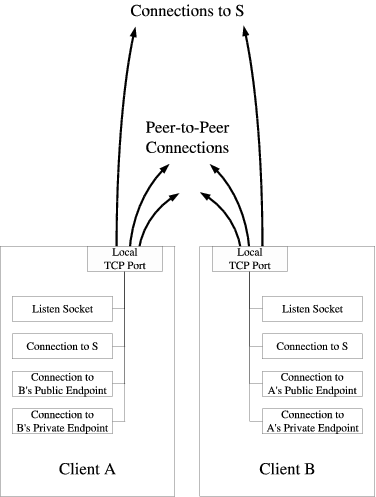

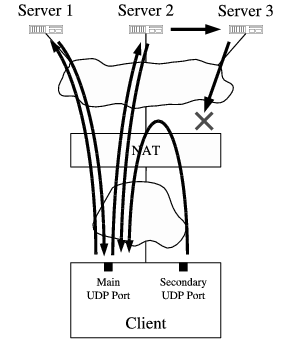

Our problem is that our two peers don’t know what the ip:port of their peer is. Worse, strictly speaking there is no ip:port until the other peer sends packets, since NAT mappings only get created when outbound traffic towards the internet requires it. We’re back to our stateful firewall problem, only worse: both sides have to speak first, but neither side knows to whom to speak, and can’t know until the other side speaks first.